The Young Lawyer · The Texan · The Revolutionists · Maverick Escapes Death · A Pioneer Bride · The Council House Massacre · Maverick Goes to Prison · Chihuahua Expedition · Maverick and Another War · The Maverick Heritage

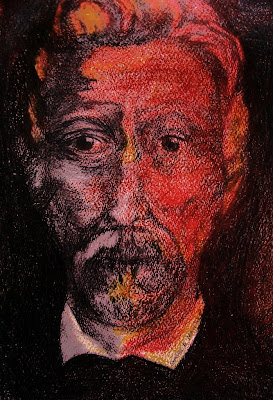

Samuel A. Maverick

Introduction

In a Frontier Society, where intellectual and educational attainments were ever rare, one with such qualities as Samuel Maverick became the indispensable man. Lawyer, businessman, landholder, and for decades a public servant in various levels of government, his accomplishments would be recognized by any generation; but his particular combination of courageousness and restlessness marked him as a natural leader for San Antonio in its years of turbulence.

Although among the first in the tradition of Texas boosters, he favored the annexation of Texas by the United States rather than continuance as an independent republic, and he favored union rather than secession prior to 1860.

Maverick became one of the great empire builders of Texas and a wealthy man. His dedication to San Antonio resulted in many personal sacrifices—the loss of personal property when the enemy invaded, gifts of money to needy persons, and always the contribution of his time and energy to the town, the Republic, and later the state of Texas.

That Samuel Maverick took a day-to-day matter-of-fact attitude in his approach to numerous hardships on the Texas frontier should suggest to the young reader in the twentieth century a valid and common sense approach to his own daily problems in a turbulent world. Indeed, this is the thesis of the authors, Kathryn and Irwin Sexton.

Mrs. Sexton had been unable to locate an appropriate book on Samuel Maverick when her young son developed an interest in this progenitor of many distinguished San Antonians. She reported her chagrin to her husband, who suggested that she begin the task of preparing such a book herself.

There resulted, as a joint enterprise, this account of a man who, in war and in economic depression, kept faith in the future of the town to which he returned from diverse adventures which were as dangerous as they are exciting for the present-day reader. Mr. and Mrs. Sexton have not ignored the contributions of Maverick's wife Mary, a pioneer gentlewoman whose spirit equaled that of her husband, and whose Memoirs provided the springboard for this biography for young people.

James W. Laurie, President

Trinity University

November, 1963

The Young Lawyer

Samuel A. Maverick, famous Texan, lived during his boyhood on a peaceful plantation in South Carolina. If he played Indians and soldiers as American boys have always done, he probably did not dream that he would one day live under the continual threat of Indians on the warpath. Nor would he have thought it possible that someday he would be shooting at Mexican soldiers from the rooftop of his own home. While studying law as a young man, he could not see ahead to the day he would help write the constitution for the Republic of Texas; and the peaceful years he spent at Yale University were in surroundings far different than those he was to find later in a Mexican prison.

Samuel A. Maverick's life might not have been as exciting, dangerous and adventurous, if he had not heard about Texas at a time when he was wondering what he should do with his life. He had intended to be a lawyer. In fact, after graduating from Yale, he had set up a law practice in Pendleton, South Carolina, in 1829. He wanted to go into politics, too. However, at this time many South Carolinians were urging that their state secede from the United States. They were aroused by the tariff laws which they felt were very unfair to the South. Both Samuel A. Maverick and his father, Samuel Maverick, were against this drastic move. Tempers were high, and Samuel and his father were active in the fight to keep South Carolina in the Union. They wrote letters to newspapers, debated at public meetings and worked hard to change public opinion. At one meeting, the elder Maverick was making a speech in answer to John C. Calhoun's arguments for secession. A young man in the audience called out slurring remarks about the speaker. Samuel, or Sam as he was called, was so angered by those taunts directed at his father that he challenged the young man to a duel. He wounded the man, and then took him into his home to care for him. Like many another young man, Sam was quick to fight; but few would have followed a duel in which they were victorious by caring for their opponent. His readiness to fight for what he believed to be right would lead him to strange places before his life was over.

That duel was a turning point in young Maverick's life. He realized then that as long as he was so opposed to the politics of the times he had little hope of being successful in public life. He withdrew from politics, from the practice of law, and from the state of South Carolina! At his father's suggestion he moved to Alabama to manage the estates of his widowed sister, Elizabeth Weyman.

Samuel A. Maverick came from a fairly well-to-do family. His father had taken an active part in the business life of Charleston, South Carolina. He is said to have been the first one to ship American cotton to England. He had retired to a quiet plantation, Montpelier, in Pendleton, South Carolina, because the climate was a more healthful one for his children. He owned much land, some of which he had signed over to his children, Samuel Augustus (born July 23, 1803), Elizabeth (born 1807), Lydia (born 1814). He found happiness in his quiet plantation life and became well known as a horticulturist. No doubt he was relieved to turn over some of the management of his and his daughters' affairs to his son. His wife, born Elizabeth Anderson of Virginia, had died when Samuel Augustus was fifteen years old.

Although very little is known of Sam's early life, it is apparent from reading the letters between him and his father that there was much affection between them. Samuel Maverick continued to give advice to his son long after he left home, but love and pride shine through his letters.

The management of Elizabeth's estates did not hold Samuel A. Maverick's interest for long. Restlessly he toured the North and visited his married sister, Lydia Van Wyck. He went to New Orleans on a business trip. In this busy port town everyone was talking about Texas which at the time belonged to Mexico, and had only been opened up to American settlers since 1820. Like many other restless young men of that time, he decided he must see the fabulous place for himself. This proved to be more than a decision to take a trip, for the pattern of his life was to be changed completely. Texas captured his imagination and fired his ambition. Texas truly became his home—he fought for it, worked for it and loved it.

The Texan

Maverick was excited by Texas, but it was the little town of San Antonio which completely won him to this new land. San Antonio was the only town of any size in the length and breadth of Texas. Velasco, on the coast, was the first Texas town he visited and there were only eight or ten families living there. The country was sparsely settled with a few isolated farms between the small settlements. While travelling he came down with malaria, and friends suggested he go to San Antonio, which had a more healthful climate.

The atmosphere and beauty of the little Spanish-Mexican town immediately charmed Maverick when he arrived in San Antonio on September 8, 1835. Although the population was under three thousand at the time, the town had a varied and colorful history. It was originally founded by the Spanish in 1718 as a fort (Presidio de Bexar), and a mission (San Antonio de Valero). The Spanish felt it was an excellent place for a settlement because of the plentiful water supplied by the San Pedro Springs and the San Antonio River. A group of colonists from the Canary Islands had also been sent to this site, and they named their settlement San Fernando de Bexar. Frequently it was called just Bexar or Bejar. Maverick usually referred to it as Bejar in his journals.

It is not surprising that San Antonio had the charm of a foreign city to Maverick, because the Spanish and Mexican influences were very apparent. He admired the charming manners of the Mexicans and their gaiety. He liked the way the adobe and stone buildings were built around open plazas. He was interested in the less prosperous homes, quaint log houses built of mesquite posts with roofs of straw or tule (a kind of rush).

No doubt, too, Maverick enjoyed the beauty of the cypresses which bordered the San Antonio River, and the quiet charm of the missions. The missions had been established by the Franciscan Fathers to teach the Indians Christianity and Spanish ways of farming. By 1800 the Franciscans had given up their mission work, but the mission churches were still used as churches. The best known was the one established as Mission San Antonio de Valero, the original name which was all but forgotten. The Mexican cavalry stationed on the mission grounds in the early 1800's was called El Alamo from the name of the town where it was recruited, San Jose Santiago del Alamo de Parras. Mission San Antonio de Valero was soon called the Alamo. It was to play an important part in Maverick's life, and in the history of San Antonio and of Texas.

Samuel A. Maverick, of course, quickly learned of the part San Antonio had played in the Mexican revolt from Spain. In the hands of first the Mexican army, then the Spanish army, it had been the scene of much fighting the discord. The revolution was drawn out from 1811 to 1821, when Mexico finally won its independence. The year before, 1820, Mexico had finally given permission to Moses Austin to settle Americans in Texas. He died shortly after that and his son, Stephen F. Austin, took over his work.

San Antonio, which had been nearly deserted at times during the Mexican Revolution, was beginning to grow and prosper when Samuel A. Maverick arrived there at the age of thirty-two. Although conditions forced him to travel far from there at times and to live away from it for many years, San Antonio was truly his home town. He contributed much to its growth and development.

It had taken Maverick from April 22 to September 8 to reach San Antonio. This was not only because of the slowness of travel by horseback, boat or wagon, but also because he stopped often along the way. He visited, he studied the land and he did business. He bought a parcel of land near Cox's Point, the first of many he was to buy in Texas. From everyone he heard about the Texan quarrels with Mexican rule.

Mexico had won its independence from Spain, but now Maverick realized another revolution was brewing. Many of the Mexican laws were as oppressive to the Mexicans living in Texas as to the Americans. Mexico's capital was far away, and it was hard to transact government business. Texans did not like the immigration laws which had been passed in the 1830's to keep American settlers from coming to Texas in too great numbers. They wanted the more liberal Mexican Constitution of 1824 and not the harsher regime of Dictator Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. There was an ever-growing number of people who were saying that the only way to bring about a more just government and the re-establishment of the 1824 constitution was to take up arms and fight.

The Revolutionists

Like many other Americans who had come to Texas out of curiosity or to find success in business ventures, Maverick soon found himself caught up in the turbulence of the times. These Americans, now Texans, were used to a democratic and representative type of government, and they were willing to fight for what they believed to be their rights.

Even if Maverick had not been an ardent believer in the Texan cause, his imprisonment by the brutal Mexicans would have made him one. Although he recorded the event in his journals factually and not emotionally, it must have shocked Maverick to find himself a captive of the Mexicans just a few short weeks after his arrival in San Antonio. He was rooming with John W. Smith when Generals Martin Perfecto de Cos and Domingo de Ugartechea marched into San Antonio. They put both Maverick and Smith under guard in Smith's house. The two generals had been ordered to San Antonio by Dictator Santa Anna. If he thought they could put out the spark of rebellion, he found he was mistaken. The militant Texans were now more than ever determined to fight.

In order to recapture San Antonio, Texan forces gathered at Mission Concepcion just outside of San Antonio. They could scarcely be called forces, this Texas army. They were volunteers, poorly organized, but eager to fight. Their commander, Stephen F. Austin, however, decided to wait for more men before attacking.

The fact that Austin was willing to lead troops against Mexico was in itself a sign that conditions in Texas had become deplorable. For years he had been a loyal citizen of Mexico. He had carefully obeyed all its laws when he was given permission to settle Americans in Texas. Then he had been imprisoned for months in Mexico because of his colonization activities. After that experience he saw the hopelessness of Texas' remaining a part of Mexico. He had previously been very much against the Texas "war party," but now he answered "yes" when asked to command the troops. He was not a military man by nature or training.

When the Texas Congress asked Austin to seek help for the revolutionists in the United States, he gave up his command to General Edward Burleson. Burleson, like Austin, waited. The Americans within San Antonio were waiting, too. Although under guard, Maverick had kept in touch with the Texas troops by sending notes back and forth with a dependable Mexican boy.

In his journal Maverick wrote how impatient he was at the situation. He could see the Mexicans fortifying the town. Cannons were being mounted at the Alamo. The streets were being well guarded. Underbrush, trees, fences—anything that could be a lurking place for Texan spies and soldiers—were being cut down. It would have been much easier to retake San Antonio with two hundred men, he wrote on November 3, 1835, than it was going to be with the fifteen hundred men Austin and Burleson were hoping would join them.

The Texan army had waited about six weeks, but they might have waited even longer if General Cos had not released Smith and Maverick. Their release was based on Smith's promise that they would soon go back to the United States, but soon proved to be not soon enough for the Mexicans! Maybe Maverick and Smith intended to keep their promise, but first they wanted to visit their friends in the Texas camp.

Once in camp, Maverick urged the already restless men to act, and volunteered to lead them into the town. After he talked, there was much discussion. First a decision was made by the officers to attack, and then the order was cancelled. He was dejected and angry at the delay and so were many of the men. Finally, Colonel Benjamin R. Milam is said to have stepped forward and asked, "Who will go with old Ben Milam into San Antonio?" Over two hundred men volunteered. At that time there were about seven hundred men in camp. Maverick estimated that over two thousand men had been there through the waiting period, but had drifted away when no action had been taken.

Just before daylight on December 5, 1835, led by Milam and Frank W. Johnson and guided by Maverick and Smith, the Texans stole into San Antonio. Maverick knew the town well, although he had only been there a short time. He knew the strength of the Mexican forces and the fortifications they had made. He even had a plan of attack. No one can be sure what the plan was, but he mentioned in his journal that he had suggested one to Austin.

Four days the battle raged. House to house they fought, and room to room. They advanced by inches as they broke through the stone walls which were usually four to five feet thick. The Americans seemed to know which houses were strategic points. Was this perhaps the plan Maverick had suggested to Austin? Some people think it might have been.

Milam was killed on the third day as he entered the Veramendi House. (A daughter of the Veramendis was married to the famous Jim Bowie.) Maverick caught Milam in his arms as he fell. So greatly did the Texans admire and depend on Milam that they tried to keep news of his death from as many of the men as possible. The doors of the Veramendi House were later placed in the Alamo. This relic of one of the battles in the Texan fight for freedom is fittingly displayed in the Alamo, "Shrine of Texas Liberty."

Although Milam was dead, General Burleson by that time had joined his men and assumed leadership of the attack. On the fifth day of fighting, Cos was captured. Maverick was a witness to the articles of capitulation signed by General Cos. The ancient adobe house in which the surrender was signed is known as the Cos House. It still stands today in La Villita, or Little Town, in San Antonio, and is visited yearly by thousands of tourists. A grandson of Maverick, Maury Maverick, was responsible for preserving this historic area.

The Texans could not possibly take care of over one thousand prisoners. Cos and his men were allowed to return to their own country after promising they would not fight against the re-establishment of the constitution of 1824. The Texans need not have bothered insisting on this promise. It wasn't kept.

Maverick Escapes Death

With San Antonio once again secure, most of the Texans left. Some joined General Sam Houston, now commanding the army of Texas, who was stationed near Goliad. Houston knew his army was too small and too ill-prepared to defend Texas against another Mexican attack which he was certain would come up too soon. He needed arms, men and time. He did not want to split up his forces by sending more men to the Alamo. Nor did he want the Mexicans to seize the cannon there for their own use or use the Alamo as a fort. For these reasons he gave orders to move the cannon to Gonzales and to destroy the Alamo. But the orders were never carried out. Colonel James Bowie delivered Houston's message to Colonel William B. Travis. Travis, the Alamo commander, did not obey these orders, but pleaded for more men. It was his firm belief that Santa Anna could be stopped at San Antonio, the first important settlement in Texas north of the Rio Grande River and Mexico. Even if they were defeated, he reasoned that the Mexicans would be delayed long enough for Houston to muster and train more men. Bowie agreed with him and stayed on at the Alamo.

Texas had so recently been opened up to Americans that everyone, it seemed, was a newcomer. Reputations were quickly established. Maverick had already proved his loyalty to the Texan cause and his qualities of leadership in the battle to retake San Antonio from General Cos. The men of San Antonio recognized in the slender young lawyer qualities of courage and intelligence, and they elected him in February, 1836, to represent them in the convention. This convention had been called to decide if Texas were to remain an independent state, faithful to the Mexican government under the constitution of 1824, or if it were to declare itself a free and sovereign nation.

Sam Maverick might well have been among his new friends who died as heroes in the battle of the Alamo. It was not lack of courage or a desire to avoid fighting which took him from the tragic scene. Travelling on horseback was a slow process and the convention in Washington-on-the-Brazos, one hundred and fifty miles away, had been called for March 1. Maverick had already started for the convention when the Mexican troops were sighted.

The Texans had heard that the Mexican army, commanded by Santa Anna himself, was on the move; but they did not realize how quickly it was approaching. The lookout sighted Mexican troops on February 23, 1836. Quickly the little band of one hundred and eighty-three men fortified themselves behind the walls of the Alamo and the siege began.

The valiant band of Texans—under the leadership of Travis, the famous Jim Bowie and the legendary Davy Crockett—withstood the siege of over twenty-four hundred Mexicans for thirteen days. On the morning of March 6, the Mexicans finally made an all-out attack on the weary men. Every man in the Alamo was killed. Only a few Mexican women, a slave boy, an American woman, Mrs. Almeron Dickinson, and her baby escaped death.

The men of the Alamo died for the freedom of Texas and set an example of bravery for the whole world, but in those days of slow communication they perished unaware that the Declaration of Independence had been signed on March 2. They did not know that their delegates had declared: "Our political connection with the Mexican nation has forever ended; and that the people of Texas do now constitute a free Sovereign and independent republic...." Because of floods, Maverick and two other delegates from San Antonio, Jose Antonio Navarro and Francisco Ruiz, had not reached Washington-on-the-Brazos until March 3. They were permitted to sign their names to the historic document, however. Maverick was the only one to sign with the name of his town, and he added after his signature "from Bejar."

Maverick stayed on at the convention as the delegates went about the difficult task of drawing up a constitution for the new nation of Texas. It was patterned after the Constitution of the United States and those of several of the states. It was said of Maverick by a fellow delegate, William Menefee, that he conducted himself as a statesman and a diplomat. His legal training and his wise political judgment contributed much to the convention. He was not a man to make a show of his knowledge and learning; but, as Menefee pointed out, it could be seen in all that he did and said. Another signer, Stephen W. Blount, wrote that when Maverick believed he was right, his strong will made him a determined man. And he was determined that Texas should be free of Mexico.

Texas had a constitution and governing officers by March 17, 1836, when the convention ended, but Santa Anna had not yet been defeated. It was not until April 21 at San Jacinto that General Sam Houston and his men defeated the Mexican forces in a surprise attack.

A Pioneer Bride

After the battle of San Jacinto, Maverick journeyed back to the United States to visit his family. By that time the tragic and heroic story of the Alamo had been heard by all America. Great was the joy of his family when they saw him.

Because of a handkerchief dropped on a muddy road, Maverick did not return to Texas as quickly as he had planned! While visiting his sister in Alabama, he rode out one day on horseback. Passing on the other side of a mudhole was a pretty young woman who dropped her handkerchief. Sam dismounted and picked it up for Mary Ann Adams. After this meeting he courted her for four months. They were married in August, 1836. Those who thought Maverick a reserved man would have been surprised at the keepsake Mary found among her husband's things after his death. Even she had not known that he kept a piece of the green muslin dress she was wearing the day they met.

Samuel's glowing accounts of life in Texas and San Antonio made his tall blonde bride anxious to see her new home. She must have had some doubts too, after hearing stories of the Cos attack, the Comanche Indian raids and the battle of the Alamo. Travel was slow and full of hardships and inconveniences. Eighteen-year-old Mary worried at the great distance that lay between Texas and her home, Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Over a year passed while they visited their families and Maverick transacted his business.

When they did start out for Texas it took them two months, from December 7, 1837, to February 4, 1838, to get there. In the party were their infant son, Sam, who had been born in October. Mary Anne's fifteen-year-old brother, Robert, six Negro servants and four of their children. They made quite a procession with their large carriage, a wagon, three saddle horses and a filly. In the wagon were the tent, their supplies, bedding—and the children. It was a long, hard journey. They stopped frequently to rest or to do the washing. Sometimes they had to wait for muddy roads to dry, and one swamp fourteen miles wide took four days to cross.

Mary must have often wondered, "When will we ever get to San Antonio?" Even when they arrived in Texas, she had to wait four months to see the picturesque town she was to call home. Samuel left her in Spring Hill on the Navidad River while he went on to see if San Antonio was safe. There was always the threat of invading Mexican troops, because Mexico continued to claim Texas and disregarded her independence. In addition, the Comanche Indians were unfriendly and made frequent raids on the town.

Maverick wrote back to Spring Hill frequently and apologized for his long delay. One of the reasons he had gone to San Antonio was to buy some land there. He was having a difficult time, he told her. There were legal technicalities complicating land purchases. He complained also that land speculators were causing all sorts of problems. He missed her greatly, he assured her again and again, but their financial future depended on his staying. The letters of Sam to Mary were often a combination of love and business!

In June when Maverick finally came to get her, all the stories Mary had heard about unfriendly Indians must have come vividly to her mind. One day as they were breaking up camp to continue on their way to San Antonio, a band of Tonkawa Indians rode up. They were coming back victorious from a battle with the Comanches. They were dressed in war paint, armed, and were displaying two scalps. These frightening men asked Mary to let them see her little "papoose," the baby Sam. She was frightened, but had the courage to say no when they wanted her to hand the baby out of the carriage to them. This was the first test of the bravery she was to show many times during the years to come. She did not show her fear. She held her baby up so the Indians might see, but she also kept her pistol and knife in sight so they would know she was prepared to defend him. All this time she kept urging Griffin, the servant, to hurry. It is easy to see why! Maverick showed his usual courage, too, and kept right on working with his men to get their equipment and possessions loaded as quickly as possible. As they left the camp site Mary's hopes that the Indians would go in the other direction were not fulfilled. The Indians accompanied them most of the night. Toward morning they left, and the rest of the journey passed without any incidents.

Texans have a reputation for boasting of their state, and Maverick was no exception. Mary's brother, Williams Adams, was so excited by Sam's stories that he had gone on to San Antonio ahead of them. His being there made Mary's arrival seem less strange.

William did not make a success of the store he owned and soon left San Antonio, though he returned later.

To have Mexicans as her only friends was an unusual experience for Mary. She wondered why other Americans didn't come to San Antonio, because they were settling in other parts of Texas. Maverick suggested that the thought of possible Indian and Mexican attacks was one reason. It was a real frontier town, she wrote home to her mother. There were still marks of bullets and cannon balls on the walls of many of the buildings.

When the Maverick family first arrived in town, they lived in a house directly across from the site of what is now the Bexar County Courthouse, but moved from there into another house. In 1839 they moved into their own home, where their second son, Lewis, was born. The main house had three rooms, and the kitchen and servants' quarters were separate. It was quite an establishment with a picket fence around the garden and grounds going down to the river. A fitting establishment, though, for the mayor of the town. In 1839, Samuel Maverick's leadership was once again recognized and he was elected mayor. San Antonio had been incorporated in January, 1837, with an area of thirty-six square miles.

Samuel Maverick, it has been said, never sought public office, nor ever electioneered for it; but from 1836 to 1867 he continually held some public office for his town and for his state. He was a scrupulously honest man, a man of learning, and had a statesman's wise and objective attitude. Undoubtedly his law training helped him carry out his public duties, but it was his staunch and upright character that made him a leader, and it was his love for San Antonio and Texas which made him accept these public duties.

The Council House Massacre

Perhaps if Maverick had lived today, he would have conducted his land transactions in an office and made decisions based on surveyors' and engineers' reports. Perhaps not, though, for Maverick greatly enjoyed the surveying camp. He was keenly interested in buying up land and was frequently away from home on survey trips. These excursions were a combination of hard work and fun for him. They were also very dangerous, because away from town there was always the threat of Indians. One time in 1839 when he left with a survey party, Mary made him promise that he would be back by a certain day. He kept his promise and returned with one or two others of the party. The night after they left camp, all but one of the group they left behind were killed by Indians.

Business frequently took Maverick to Alabama and South Carolina. The trips were long, and must have seemed even longer to Mary, left alone with the children, than they did to him. Although mail service was slow and irregular, he wrote often. The letters reveal him as a loving and good husband who worried about his family. He was concerned for them and deplored the business which took him away. Sam's father frequently wrote his son that health and life were more important than money. Maverick, a man of many interests and much energy, did not heed his father's advice and continued to travel on business. He usually shopped for his wife on these trips as supplies were scarce. Mary's shopping lists included everything from silver spoons and tea kettles to lard and pins, clothing and medicines. Maverick was generous to his family. His bounteous gifts to the city of San Antonio also amply testify to his generosity.

On the day of the Council House Massacre, Mary must have been especially glad that her husband was not away on one of his trips. March 19, 1840, was the date of that bloody and infamous fight. For some time past, the Comanche Indians had been very troublesome. In their raids on weak settlements, they had captured many white people. On this warm spring day the Indians had come into San Antonio supposedly to make a peace treaty. They met at the Council House, the courthouse of that time which stood near the site of the present Bexar County Courthouse. While discussing terms, the Indians suddenly drew their arrows and commenced firing. Everyone ran out into the public square. Soldiers were shooting. Civilians were running to get arms. Indians were trying to escape to the river.

Mary frantically looked for the boys. They were in the yard, and so was an Indian! The maid, Ginny, stood there with a rock in her hand to defend her own children and the two Maverick boys. The Indian hesitated, then ran on to the river. A bullet from Andrew's gun killed him as he jumped into the river. By this time there was much hand-to-hand fighting. Mary, watching one fight, got so excited that she ran out of the house. One of the officers ordered her to get back. She explains in her memoirs that she was young at the time, just twenty-two years old, and was curious.

Maverick had made a wise choice for a wife, for she met danger fearlessly and suffered loneliness and hardship without complaint. Thirty-three Indians were killed the day of the Council House Massacre and thirty-three were taken prisoner. Six Americans were killed and one Mexican; ten Americans were wounded. The Indians had been given opportunities to surrender, but did not.

Despite the constant threat of Indians, more Anglo-Americans were moving into San Antonio; and Mary had many good times with her women friends, both Mexican and American. They had picnics and bathing parties. They felt safer because Jack Hays and his "boys" were guarding the town. From 1838 to 1848 Maverick was one of Hays' "minutemen" and often went on Indian skirmishes and other expeditions.

Jack Hays had come to Texas from Tennessee as a surveyor when he was only nineteen years old. He had soon earned a reputation for courage and skill at Indian fighting. When he was only twenty-three, the Texas congress commissioned him as the first captain of the Texas Rangers. The Rangers were created to defend the isolated frontiers to the south and west and they became famous under his command. The slim, dark-complexioned young man was quiet and courteous and well liked, but to the Indians he was a man to be feared.

Maverick Goes to Prison

The year 1841 brought a welcome peace to the Mavericks and San Antonio, but it did not last long. In 1842 the people of the little town suffered one of their worst years. In February Captain Hays heard that Mexican troops had crossed over the Rio Grande. Most of the ladies and children left quickly. They took what possessions they had room for in their wagons and carriages. The Mavericks left their house in the care of two gentlemen who were to live in it. Mary entrusted her valuables to a neighbor. Little did they thinnk that she would not reclaim them for five years.

The group of refugees was still near Seguin, about thirty-five miles away, when they heard that San Antonio had fallen to General Rafael Vasquez. The women were all extremely upset until they heard that their husbands were all right and that Hays had recaptured the town within three days.

Maverick quickly joined his family after the victory and settled them in Gonzales. Their journey was a difficult one. Rains slowed their progress. They stayed at various homes along the way—once they slept in a corn crib. One night as they slept on the floor it was not only Mary's damp clothing that kept her awake, but the sound of the hogs under the floor! Maverick left them again to return to San Antonio. He rejoined them in April saying that their home had been robbed. It had been stripped of everything in it, including a walnut mantlepiece built into the wall.

The Mavericks decided they would move temporarily to a place near La Grange on the Colorado River, because San Antonio was under the constant threat of another Mexican attack. Sam did not stay long, however, because he had to make an extended business trip to the United States. When he returned, he brought Mary's sister, Elizabeth, to stay with them, much to Mary's delight.

Court was in session in San Antonio so Maverick returned for it and to perform his duties as city treasurer. Mary mourned his leaving her, their two sons and their baby daughter Agatha, who had been born in 1841. Perhaps his blue-eyed Mary had a presentiment of events to come; perhaps it was only her experience of the past few years which made her so reluctant to have him go. He admitted afterwards in a letter that she had almost persuaded him to stay.

By the end of the summer Mary had good reason to wish she had persuaded him to remain. The Mexicans under General Adrian Woll made a surprise attack on San Antonio on September 11, 1842, with thirteen hundred men. Court was in session that day, with Samuel Maverick representing Dr. Shields Booker. The doctor was suing the city for fifty pesos, which, he said, had been promised him by the mayor, Juan Seguin. Judge Anderson Hutchinson was presiding over the court and all members of the San Antonio Bar were present.

When the Texans realized that the town was being attacked, they quickly fortified themselves in the Maverick home. Some of them shot at Mexican troops from the roof. They knew they were outnumbered and were ill-prepared in every way to wage a battle. Grave indeed was their plight; and, as they discussed it, they realized that to surrender was their only choice. They surrendered. Fifty-two men were taken prisoner, including Dr. Booker, whose case was before the court. The case was never completed.

The prisoners were kept in San Antonio for four days; then General Woll ordered them to the Perote Prison deep in Mexico. The trip was arduous, but they were allowed horses; in fact, Maverick started the long trek on his own horse. The alert Maverick kept his journal during this time. It was filled with details about the beauty of the land and the kind of crops and the irrigation. He commented on the towns, and noted the number of miles they travelled each day. Many another man would have been too discouraged about the future—and his present difficulties—to take an interest in such things.

Maverick's slave, Griffin, had hurried to La Grange to tell Mary the sad news. They decided that he should follow his beloved master into Mexico. With gun, mule and money he set out. He never reached the prisoners. En route he became engaged in a terrible battle east of San Antonio, which was later called the Dawson Massacre. The Mavericks all mourned deeply when they heard that he had been killed after fighting very courageously. The Texans finally succeeded in forcing General Woll to evacuate San Antonio. The Mexican Army retreated into Mexico.

Life in prison was a trying experience for the men of San Antonio. They were forced to do backbreaking work. Their guards were cruel. The captain of the prison maintained a store, and sold to the prisoner the supplies that should have been issued to them. Soon they had no money to buy anything. Those who could pay for it had been given a little better headquarters, but Maverick scorned such an arrangement. He believed that all of them were there for the same reason and that they should stay together sharing a common fate.

At first Maverick refused to work because the food, and the small quantities of it, did not give the prisoners strength enough to haul sand and load bricks. He was put in a dungeon for his rebellion and was kept in solitary confinement on meager rations. He was finally released and ordered to act as a supervisor of the others. The thin broth, the moldy bread and the almost inedible meat were scarcely nourishing enough to live on. Yet his letters home were written to cheer his beloved wife, and he assured her these rations were keeping him at a good weight. She was not to despair, he told her. She should look after herself and go riding with her sister so that she would stay healthy and happy.

Maverick, who escaped death at the Alamo, and who missed by a few hours being massacred by Indians, was once again fortunate. He was related by marriage to General Waddy Thompson, the United States minister to Mexico. It is typical of the kind of man Maverick was that he did not ask Thompson to work for his release. His father and others asked for him, however. General Thompson went to Santa Anna, himself, to ask for the release of Maverick, W. E. Jones and Judge Hutchinson. He also tried to get the others released. In his memoirs General Thompson wrote that he asked Maverick if he would announce that he was for the re-annexation of Texas by Mexico. If he would Thompson was sure he would be released.

True to his beliefs and ideals, Maverick's answer was a firm no. Another prisoner, James W. Robinson, did not share Maverick's attitude. The former lieutenant governor of Texas was released to discuss with President Sam Houston the terms that Santa Anna was willing to settle for—peace for Texas if it would recognize Mexican sovereignty.

While in prison Maverick wrote an extremely forceful letter to the Mexican secretary of state. Jose Maria Bocanegra, in which he declared himself to be Bocanegra's public enemy! He described exactly what the men had to eat; why they had to have more and better food; described the cruelty of the guards and the dishonesty of the man in charge of the prison; and detailed the reasons why he felt their imprisonment was a mistake, illegal and dishonorable. He asked General Thompson to deliver this letter, but the man to whom it was written never read it. Thompson was certain such a letter would only harm Maverick's chances for release!

Life in prison was made even harder for Maverick because he did not hear from his family for six months, although he kept writing to them. The lack of information about affairs in Texas also worried him, for he heard many conflicting rumors. He wrote to Mary that as long as he had no facts to keep his mind busy, he had much time for reflecting and for remembering only happy times.

Maverick immediately wrote to Mary when he was told that after seven months in prison he, Jones and Hutchinson were to be released. He told her that he would stop in New Orleans and she should write a letter there listing the supplies she needed and he would buy them. On the brink of a freedom he had almost despaired of getting, he remembered to ask her the size of his children's shoes so that he could buy them some. Truly he was a family man as well as an acute businessman and respected political leader.

Maverick, Jones and Hutchinson had to report to Mexico City after their release, but by May 4, 1843, were finally home once more with their families. Mary, of course, was delighted to see him, but shuddered at his chain which he gave her as a souvenir. He was elated to see his second daughter, Augusta, who was born in March, 1843. His joy was mixed with sorrow for the friends left behind in prison. It was almost with a feeling of shame, he said, that he lived as a free man while they were suffering the hardships of prison life. One of his fellow prisoners wrote that conditions were even worse after the three of them had been released. However, General Thompson was still working for them. He was successful and two month later, on June 16, 1843, the others from San Antonio were set free.

Chihuahua Expedition

On his return from Perote, Maverick bought a ranch on the Matagorda Peninsula. He was not at home long with his family. Although still a prisoner at the time of elections, he had been elected a senator. He was also serving as alderman for San Antonio, an office he held from 1841 through 1844. In December, 1843 he was in Washington-on-the-Brazos, serving in what was to be the last session of the last congress of the Republic of Texas. After it adjourned, he went to South Carolina on business. He did spend some time at home that year, but even at home he narrowly escaped death. While sailing on the Gulf, his boat was caught in a sudden squall. He and his friends were nearly drowned when the boat capsized. Luckily it happened near the shore and they were rescued.

Maverick ardently believed in Texas and urged his friends to buy land and settle there. Occasionally he became very annoyed at the ill-informed questions his friends and acquaintances in the United States would ask. He worked hard for the new republic as a legislator, but felt that Texas would be far better off as a part of the United States rather than an independent country. He was convinced that annexation of Texas by the United States would be to the benefit of both countries. Some Texan leaders shared his beliefs. Still another group, however, fought annexation. Finally those who wanted annexation were successful, and Texas became the twenty-eighth state in the Union on December 29, 1845. For ten years Texas had flown the Lone Star flag as an independent country.

Although the Mavericks had lived away from San Antonio since General Woll's attack and had bought a ranch on the Peninsula, San Antonio was their real home. Maverick was constantly there as he became more and more involved in San Antonio's business life.

Mary had her first ride in a stagecoach when they finally moved back to San Antonio in October 1847. She took their two-year-old son, George, their daughter, Agatha, and Lizzie, her sister, with her. Maverick took the rest of the family, the servants and the provisions in a wagon. After a five-year absence Mary was surprised to see so many new residents. People seemed to be arriving daily. With Texas a part of the United States, Mexico had finally stopped her attempts to reclaim it. Indian attacks were not as much of a threat, for a great many Indians had been removed to reservations. A peaceful San Antonio attracted people and the population which numbered eight hundred in 1846 jumped to over three thousand by 1850.

The Mavericks were happy to be back in their old home which now had dirt floors because the cement had worn off. Their son, William or "Willie," was born there December 1847. Sorrow soon entered into it, however, when Agatha, the oldest of their daughters, died at the age of seven. Maverick was out on a surveying party locating some headrights. She had not been taken ill until after he had left. They had no way to let him know that she had been sick, or that she had died. He was on his way back into town almost three weeks later when someone along the road told him of her death. The shock of hearing the news in this way and his terrible grief at her death made him a changed man. He was silent. He was sad. He blamed himself for being away when she died. He took no interest in anything.

Mary and his many friends were very worried about him. Jack Hay's, now a colonel, suggested to Mary that she urge Maverick to go with him on a proposed expedition to El Paso. Mary was reluctant. She didn't want him to leave his family again. She did not think he was well enough to undertake such a difficult trip. Hays reminded her that her husband had always enjoyed life in the open. He felt that going on this expedition whose purpose was to open up a better and shorter trading route through the wilds of El Paso would help Maverick overcome his grief. Mary was finally persuaded. At her urging Maverick went along with the famous Chihuahua Expedition. El Paso was the Texas border town across from Chihuahua's principal commercial town, El Paso Del Norte (later named Juarez).

It was a severe trip for the fifty men and their fifteen Delaware Indian guides. When the party lost its way, Maverick partly forgot his grief in his efforts to keep alive. They were forced to eat strange things in order to survive—grass soup, roots, berries, mule meat and polecats. They chewed leather and the tops of their boots to keep their mouths moist when there was no water.

Maverick made only brief entries in his journal on this expedition. He noted the number of miles they travelled and their route. Thirst was the word he used most frequently! Their lack of water was almost worse than the lack of food. The mustang meat wasn't very good, he reported. One of the men in their party went insane because of the terrible conditions. When he wandered off from camp, they took the time to search for him but they did not succeed in finding him.

The half-starved men might have died had it not been for the friendly Indians they met, who guided them on to El Paso. The return journey was much easier, although they had one skirmish with unfriendly Indians. The dangers and the hardships of those three and a half months helped Maverick. He was more like his old self when he returned, but he never seemed to get over his grief for Agatha entirely. He had helped Texas once more, too, because the party had opened up a better trading route to El Paso and Chihuahua, Mexico.

Maverick and Another War

Terror came to San Antonio when the dreaded cholera swept the town in 1849. Over six hundred people died during the six weeks the epidemic lasted. Death came to nearly every family including the Mavericks, whose daughter Augusta died.

For some time Maverick had wanted his home on the ground of the Alamo or near them. The place—where his friends had met the fate that so easily could have been his—had a fascination for him. Now he was even more determined because he felt that living on the higher ground there would be more healthful for his family.

There was considerable disagreement about the ownership of the Alamo. The army claimed it and so did the city. Because it had been used as a fort for so many years, the fact that it had originally been a mission had been forgotten. Maverick, a man of great determination and a man of action, set out to prove to the authorities that the Alamo was a part of the Mission San Antonio de Valero. He finally convinced them. The church leased the Alamo and grounds then until the state of Texas bought it in 1883. At Maverick's request F. Giraud surveyed the site in 1849. Historians still accept his map, which shows the boundary as the inner line of buildings around the wall.

Maverick built his new home on the northwest corner within the old walls of the mission, but outside the boundary line as set by Giraud. Until they moved into the new house, the Mavericks lived in an old Mexican house on the grounds where a son, John Hay, was born. He only lived a few months.

When their new home was finished in 1850, it had two stories, two rooms up, two down, built of stone and of good size. There a daughter, Mary, was born in 1851. Travis Park, in the downtown section of San Antonio, was part of their orchard. San Antonio at that time had a population of thirty-five hundred.

Maverick had been a member of the last congress of the Republic of Texas, and in 1851 he was elected to the fourth legislature of the state of Texas as a member of the house of representatives. He served again in the fifth session. In addition to his public duties, he was active in business and was still practicing law as he had since he first took out a law license in San Antonio in 1838. Truly, he was a busy man; but he always had time for his family, too. They enjoyed driving in the country in the horse and buggy he had bought for them. The children were going to school and attending dancing class. Mary, as women have ever done, was busy raising money for the church by helping to give suppers.

Although Samuel Maverick helped make the early history of Texas and was one of the state's outstanding political and business leaders, when people hear the name Maverick, they often think first of the word "maverick." Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary gives two meanings: (1) "An unbranded animal, esp. a motherless calf, formerly customarily claimed by the one first branding it. (2) Colloq. A refractory or recalcitrant individual who bolts his party or group and initiates an independent course." How did this man—whose business interests were not primarily those of a rancher, (although he owned a ranch), whose manner was well reserved and who brought to politics a seasoned, well-balanced and wise mind—happen to have his name used either for unbranded cows or recalcitrant persons? It's an interesting story.

In 1847 Maverick accepted four hundred head of cattle in payment of a twelve-hundred-dollar debt. He kept them on his ranch on the Matagorda Peninsula. When they moved back to San Antonio, he left the ranch and the cattle in charge of his slave, Jack. Jack, it seems, was careless about his work and let the cattle stray.

In 1854 Maverick had the cattle moved to Conquista Ranch which he had established on the bank of the San Antonio River about fifty miles below San Antonio. He probably had the cattle branded at the time they were transferred. Branding was necessary to establish ownership when cattle ranges were not fenced and unbranded cattle could be claimed by anyone. The cattle were wild, and they strayed because Jack continued to neglect his work.

Jack's laziness caused trouble when Maverick sold the cattle to A. Toutant Beauregard some two years later in 1856. Part of the contract was that Beauregard was to round up all the cattle. It was a difficult roundup. Whenever an unbranded yearling was found, they assumed it was Maverick's, or, as they began to say, "a maverick." They branded all of these. Cowboys carried the story in their travels and the term "maverick" was soon used by cowboys all over the United States for any unbranded cattle.

Eventually the word "maverick" was extended to include human strays, that is, people who do not conform, who stray away from the "brand" of an established group or a traditional way of thinking.

The years from 1854 to the outbreak of the Civil War were more peaceful ones. San Antonio was growing and prospering, with a population of eight thousand in 1860. Maverick, always a leader in the financial progress of his city, became a director of the S. A. and M. G. Railroad.

Samuel and Mary Maverick were busy, but often lonesome for their two oldest sons, Sam and Lewis. Sam was in college in Scotland, and Lewis was in a Vermont college. There were still children at home. Two were babies, Albert, born in 1854, and Elizabeth, in 1857. Personal tragedy came once again when Elizabeth died at the age of two.

Another tragedy—nation-wide—was in the making too. Maverick was very much concerned with the political strife in those years before the Civil War. He served as a senator in the state legislature from 1855 through 1858 and in the House of Representatives during the eight session, which met in 1859. Texas was Southern in its attitude toward slavery, for it had been settled primarily by people from the Southern states. Many of its leaders were planters who were chiefly pro-slavery. It was their belief that the South—and Texas—must leave the United States.

Texas had its group of ardent Union men, too, but they were in the minority. On January 28, 1861, when the legislature met in extraordinary session, it passed a resolution 152 to 6 "that the State of Texas should separately secede from the Federal Union." In February the people of Texas voted for it overwhelmingly, 46,129 to 14,679. Secession went officially into effect in March, 1861, just twenty-five years after Texas independence from Mexico had been declared at Washington-on-the-Brazos. Texas joined with the other Southern states in the Confederate States of America. The Confederate flag was the sixth to fly over Texas succeeding the flags of France, Spain, Mexico, the Republic of Texas and the United States.

Maverick was a member of the ninth legislature which had voted on secession. Remembering that as a young man he had given up a political life in South Carolina because of the controversy about secession, one would have thought his vote would have been recorded as no. He voted yes. Why? Had his views so radically changed? Was he going along with what he considered would be a majority? Knowing Samuel Maverick to be a man of integrity, the answer to the last question must be a firm no. But in many ways his views had changed. It has been said that the Union guaranteed and protected the sovereignty of the states which made up the Union, and protected the rights of citizens. Once he decided that this sovereignty and these rights were not being maintained in the Union, then he was in favor of secession. It was still a difficult decision for him as it was for so many other men during those perilous times. He did what he thought was right, but it caused him pain.

In February of 1861, Maverick was appointed to the Committee on Public Safety which demanded the surrender of the Union army and all garrisons in Texas, including, of course, those at San Antonio. To their great credit the committee managed this difficult task without bloodshed. It was a peaceful withdrawal, and Texas was spared the destruction which befell other Southern states. Four sons of the Mavericks, George, Sam, Lewis and Willie, saw service in the Civil War. The letters exchanged between them and their parents during this difficult time reveal a wonderful feeling of affection. The Mavericks were a family who enjoyed each other.

In 1862 Maverick once again served as mayor of San Antonio. In 1863 he became the chief justice of Bexar County. For thirty-two years he served in many public capacities.

On September 2, 1870, Samuel A. Maverick died, having given bountifully of his time and energies to his home town and to his state.

The Maverick Heritage

Maverick was called one of the "empire builders of Texas" and at his death was said to be one of the largest landholders in the United States. Although he was a successful businessman, he did not work solely for personal benefit. He gave of his money and possessions to the city he loved and its citizens. Some gifts he gave anonymously, but others are known. At his death he left land for the Alamo Literary Society, of which he was a charter member. In 1858 he had donated four city blocks to St. Mark's Episcopal Church for a building. He also gave to this church a 526-pound bell cast from a cannon buried on the Alamo grounds. He asserted this was one buried by the revolutionists in 1831 and not one used in the famous battle of the Alamo. To the city he gave his orchard, now Travis Park. He gave other gifts of land to benefit his city and to encourage business. He gave large gifts to charity, too. Texas honored his contributions to the state by naming a county for him.

The name Maverick is one not forgotten for Samuel Maverick's children also did much for his city and country. Sam was a prominent businessman, as was Albert. William also served as alderman and one of his sons was a member of the U. S. Diplomatic Service. George promoted the cause of railroads before he left San Antonio to practice law in St. Louis, Missouri. George's daughter, Rena Green, prominent in San Antonio's life, was the editor of Mary Maverick's memoirs which tell us so much about Maverick. His daughter Mary married Edwin H. Terrell, United States ambassador to Belgium. Albert, who was active in building activities in the business center of town, was also an ardent conservationist. His son Maury, Samuel A. Maverick's grandson, was a prominent Texas political figure. He served in the United States Congress and as mayor of San Antonio. He was interested in preserving old San Antonio and was responsible for the law which made San Jose Mission a national historic site in 1935. When mayor, he obtained authority from the federal government in 1939 to restore La Villita, the old town. Maury Maverick, Jr., Maury's son, is well known in political and business circles in Texas.

The Mavericks are a splendid example of a fine American family. They have lived up to the reputation Samuel Maverick established. Like him, they have worked for their city, state and country in public and in private life. Samuel Maverick, a just man, a man of integrity, a man of honor, has lived on in them.

Kathyryn and Irwin Sexton

Samuel A. Maverick

Introduction

In a Frontier Society, where intellectual and educational attainments were ever rare, one with such qualities as Samuel Maverick became the indispensable man. Lawyer, businessman, landholder, and for decades a public servant in various levels of government, his accomplishments would be recognized by any generation; but his particular combination of courageousness and restlessness marked him as a natural leader for San Antonio in its years of turbulence.

Although among the first in the tradition of Texas boosters, he favored the annexation of Texas by the United States rather than continuance as an independent republic, and he favored union rather than secession prior to 1860.

Maverick became one of the great empire builders of Texas and a wealthy man. His dedication to San Antonio resulted in many personal sacrifices—the loss of personal property when the enemy invaded, gifts of money to needy persons, and always the contribution of his time and energy to the town, the Republic, and later the state of Texas.

That Samuel Maverick took a day-to-day matter-of-fact attitude in his approach to numerous hardships on the Texas frontier should suggest to the young reader in the twentieth century a valid and common sense approach to his own daily problems in a turbulent world. Indeed, this is the thesis of the authors, Kathryn and Irwin Sexton.

Mrs. Sexton had been unable to locate an appropriate book on Samuel Maverick when her young son developed an interest in this progenitor of many distinguished San Antonians. She reported her chagrin to her husband, who suggested that she begin the task of preparing such a book herself.

There resulted, as a joint enterprise, this account of a man who, in war and in economic depression, kept faith in the future of the town to which he returned from diverse adventures which were as dangerous as they are exciting for the present-day reader. Mr. and Mrs. Sexton have not ignored the contributions of Maverick's wife Mary, a pioneer gentlewoman whose spirit equaled that of her husband, and whose Memoirs provided the springboard for this biography for young people.

James W. Laurie, President

Trinity University

November, 1963

The Young Lawyer

Samuel A. Maverick, famous Texan, lived during his boyhood on a peaceful plantation in South Carolina. If he played Indians and soldiers as American boys have always done, he probably did not dream that he would one day live under the continual threat of Indians on the warpath. Nor would he have thought it possible that someday he would be shooting at Mexican soldiers from the rooftop of his own home. While studying law as a young man, he could not see ahead to the day he would help write the constitution for the Republic of Texas; and the peaceful years he spent at Yale University were in surroundings far different than those he was to find later in a Mexican prison.

Samuel A. Maverick's life might not have been as exciting, dangerous and adventurous, if he had not heard about Texas at a time when he was wondering what he should do with his life. He had intended to be a lawyer. In fact, after graduating from Yale, he had set up a law practice in Pendleton, South Carolina, in 1829. He wanted to go into politics, too. However, at this time many South Carolinians were urging that their state secede from the United States. They were aroused by the tariff laws which they felt were very unfair to the South. Both Samuel A. Maverick and his father, Samuel Maverick, were against this drastic move. Tempers were high, and Samuel and his father were active in the fight to keep South Carolina in the Union. They wrote letters to newspapers, debated at public meetings and worked hard to change public opinion. At one meeting, the elder Maverick was making a speech in answer to John C. Calhoun's arguments for secession. A young man in the audience called out slurring remarks about the speaker. Samuel, or Sam as he was called, was so angered by those taunts directed at his father that he challenged the young man to a duel. He wounded the man, and then took him into his home to care for him. Like many another young man, Sam was quick to fight; but few would have followed a duel in which they were victorious by caring for their opponent. His readiness to fight for what he believed to be right would lead him to strange places before his life was over.

That duel was a turning point in young Maverick's life. He realized then that as long as he was so opposed to the politics of the times he had little hope of being successful in public life. He withdrew from politics, from the practice of law, and from the state of South Carolina! At his father's suggestion he moved to Alabama to manage the estates of his widowed sister, Elizabeth Weyman.

Samuel A. Maverick came from a fairly well-to-do family. His father had taken an active part in the business life of Charleston, South Carolina. He is said to have been the first one to ship American cotton to England. He had retired to a quiet plantation, Montpelier, in Pendleton, South Carolina, because the climate was a more healthful one for his children. He owned much land, some of which he had signed over to his children, Samuel Augustus (born July 23, 1803), Elizabeth (born 1807), Lydia (born 1814). He found happiness in his quiet plantation life and became well known as a horticulturist. No doubt he was relieved to turn over some of the management of his and his daughters' affairs to his son. His wife, born Elizabeth Anderson of Virginia, had died when Samuel Augustus was fifteen years old.

Although very little is known of Sam's early life, it is apparent from reading the letters between him and his father that there was much affection between them. Samuel Maverick continued to give advice to his son long after he left home, but love and pride shine through his letters.

The management of Elizabeth's estates did not hold Samuel A. Maverick's interest for long. Restlessly he toured the North and visited his married sister, Lydia Van Wyck. He went to New Orleans on a business trip. In this busy port town everyone was talking about Texas which at the time belonged to Mexico, and had only been opened up to American settlers since 1820. Like many other restless young men of that time, he decided he must see the fabulous place for himself. This proved to be more than a decision to take a trip, for the pattern of his life was to be changed completely. Texas captured his imagination and fired his ambition. Texas truly became his home—he fought for it, worked for it and loved it.

The Texan

Maverick was excited by Texas, but it was the little town of San Antonio which completely won him to this new land. San Antonio was the only town of any size in the length and breadth of Texas. Velasco, on the coast, was the first Texas town he visited and there were only eight or ten families living there. The country was sparsely settled with a few isolated farms between the small settlements. While travelling he came down with malaria, and friends suggested he go to San Antonio, which had a more healthful climate.

The atmosphere and beauty of the little Spanish-Mexican town immediately charmed Maverick when he arrived in San Antonio on September 8, 1835. Although the population was under three thousand at the time, the town had a varied and colorful history. It was originally founded by the Spanish in 1718 as a fort (Presidio de Bexar), and a mission (San Antonio de Valero). The Spanish felt it was an excellent place for a settlement because of the plentiful water supplied by the San Pedro Springs and the San Antonio River. A group of colonists from the Canary Islands had also been sent to this site, and they named their settlement San Fernando de Bexar. Frequently it was called just Bexar or Bejar. Maverick usually referred to it as Bejar in his journals.

It is not surprising that San Antonio had the charm of a foreign city to Maverick, because the Spanish and Mexican influences were very apparent. He admired the charming manners of the Mexicans and their gaiety. He liked the way the adobe and stone buildings were built around open plazas. He was interested in the less prosperous homes, quaint log houses built of mesquite posts with roofs of straw or tule (a kind of rush).

No doubt, too, Maverick enjoyed the beauty of the cypresses which bordered the San Antonio River, and the quiet charm of the missions. The missions had been established by the Franciscan Fathers to teach the Indians Christianity and Spanish ways of farming. By 1800 the Franciscans had given up their mission work, but the mission churches were still used as churches. The best known was the one established as Mission San Antonio de Valero, the original name which was all but forgotten. The Mexican cavalry stationed on the mission grounds in the early 1800's was called El Alamo from the name of the town where it was recruited, San Jose Santiago del Alamo de Parras. Mission San Antonio de Valero was soon called the Alamo. It was to play an important part in Maverick's life, and in the history of San Antonio and of Texas.

Samuel A. Maverick, of course, quickly learned of the part San Antonio had played in the Mexican revolt from Spain. In the hands of first the Mexican army, then the Spanish army, it had been the scene of much fighting the discord. The revolution was drawn out from 1811 to 1821, when Mexico finally won its independence. The year before, 1820, Mexico had finally given permission to Moses Austin to settle Americans in Texas. He died shortly after that and his son, Stephen F. Austin, took over his work.

San Antonio, which had been nearly deserted at times during the Mexican Revolution, was beginning to grow and prosper when Samuel A. Maverick arrived there at the age of thirty-two. Although conditions forced him to travel far from there at times and to live away from it for many years, San Antonio was truly his home town. He contributed much to its growth and development.

It had taken Maverick from April 22 to September 8 to reach San Antonio. This was not only because of the slowness of travel by horseback, boat or wagon, but also because he stopped often along the way. He visited, he studied the land and he did business. He bought a parcel of land near Cox's Point, the first of many he was to buy in Texas. From everyone he heard about the Texan quarrels with Mexican rule.

Mexico had won its independence from Spain, but now Maverick realized another revolution was brewing. Many of the Mexican laws were as oppressive to the Mexicans living in Texas as to the Americans. Mexico's capital was far away, and it was hard to transact government business. Texans did not like the immigration laws which had been passed in the 1830's to keep American settlers from coming to Texas in too great numbers. They wanted the more liberal Mexican Constitution of 1824 and not the harsher regime of Dictator Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. There was an ever-growing number of people who were saying that the only way to bring about a more just government and the re-establishment of the 1824 constitution was to take up arms and fight.

The Revolutionists

Like many other Americans who had come to Texas out of curiosity or to find success in business ventures, Maverick soon found himself caught up in the turbulence of the times. These Americans, now Texans, were used to a democratic and representative type of government, and they were willing to fight for what they believed to be their rights.

Even if Maverick had not been an ardent believer in the Texan cause, his imprisonment by the brutal Mexicans would have made him one. Although he recorded the event in his journals factually and not emotionally, it must have shocked Maverick to find himself a captive of the Mexicans just a few short weeks after his arrival in San Antonio. He was rooming with John W. Smith when Generals Martin Perfecto de Cos and Domingo de Ugartechea marched into San Antonio. They put both Maverick and Smith under guard in Smith's house. The two generals had been ordered to San Antonio by Dictator Santa Anna. If he thought they could put out the spark of rebellion, he found he was mistaken. The militant Texans were now more than ever determined to fight.

In order to recapture San Antonio, Texan forces gathered at Mission Concepcion just outside of San Antonio. They could scarcely be called forces, this Texas army. They were volunteers, poorly organized, but eager to fight. Their commander, Stephen F. Austin, however, decided to wait for more men before attacking.

The fact that Austin was willing to lead troops against Mexico was in itself a sign that conditions in Texas had become deplorable. For years he had been a loyal citizen of Mexico. He had carefully obeyed all its laws when he was given permission to settle Americans in Texas. Then he had been imprisoned for months in Mexico because of his colonization activities. After that experience he saw the hopelessness of Texas' remaining a part of Mexico. He had previously been very much against the Texas "war party," but now he answered "yes" when asked to command the troops. He was not a military man by nature or training.

When the Texas Congress asked Austin to seek help for the revolutionists in the United States, he gave up his command to General Edward Burleson. Burleson, like Austin, waited. The Americans within San Antonio were waiting, too. Although under guard, Maverick had kept in touch with the Texas troops by sending notes back and forth with a dependable Mexican boy.

In his journal Maverick wrote how impatient he was at the situation. He could see the Mexicans fortifying the town. Cannons were being mounted at the Alamo. The streets were being well guarded. Underbrush, trees, fences—anything that could be a lurking place for Texan spies and soldiers—were being cut down. It would have been much easier to retake San Antonio with two hundred men, he wrote on November 3, 1835, than it was going to be with the fifteen hundred men Austin and Burleson were hoping would join them.

The Texan army had waited about six weeks, but they might have waited even longer if General Cos had not released Smith and Maverick. Their release was based on Smith's promise that they would soon go back to the United States, but soon proved to be not soon enough for the Mexicans! Maybe Maverick and Smith intended to keep their promise, but first they wanted to visit their friends in the Texas camp.

Once in camp, Maverick urged the already restless men to act, and volunteered to lead them into the town. After he talked, there was much discussion. First a decision was made by the officers to attack, and then the order was cancelled. He was dejected and angry at the delay and so were many of the men. Finally, Colonel Benjamin R. Milam is said to have stepped forward and asked, "Who will go with old Ben Milam into San Antonio?" Over two hundred men volunteered. At that time there were about seven hundred men in camp. Maverick estimated that over two thousand men had been there through the waiting period, but had drifted away when no action had been taken.

Just before daylight on December 5, 1835, led by Milam and Frank W. Johnson and guided by Maverick and Smith, the Texans stole into San Antonio. Maverick knew the town well, although he had only been there a short time. He knew the strength of the Mexican forces and the fortifications they had made. He even had a plan of attack. No one can be sure what the plan was, but he mentioned in his journal that he had suggested one to Austin.

Four days the battle raged. House to house they fought, and room to room. They advanced by inches as they broke through the stone walls which were usually four to five feet thick. The Americans seemed to know which houses were strategic points. Was this perhaps the plan Maverick had suggested to Austin? Some people think it might have been.

Milam was killed on the third day as he entered the Veramendi House. (A daughter of the Veramendis was married to the famous Jim Bowie.) Maverick caught Milam in his arms as he fell. So greatly did the Texans admire and depend on Milam that they tried to keep news of his death from as many of the men as possible. The doors of the Veramendi House were later placed in the Alamo. This relic of one of the battles in the Texan fight for freedom is fittingly displayed in the Alamo, "Shrine of Texas Liberty."

Although Milam was dead, General Burleson by that time had joined his men and assumed leadership of the attack. On the fifth day of fighting, Cos was captured. Maverick was a witness to the articles of capitulation signed by General Cos. The ancient adobe house in which the surrender was signed is known as the Cos House. It still stands today in La Villita, or Little Town, in San Antonio, and is visited yearly by thousands of tourists. A grandson of Maverick, Maury Maverick, was responsible for preserving this historic area.

The Texans could not possibly take care of over one thousand prisoners. Cos and his men were allowed to return to their own country after promising they would not fight against the re-establishment of the constitution of 1824. The Texans need not have bothered insisting on this promise. It wasn't kept.

Maverick Escapes Death

With San Antonio once again secure, most of the Texans left. Some joined General Sam Houston, now commanding the army of Texas, who was stationed near Goliad. Houston knew his army was too small and too ill-prepared to defend Texas against another Mexican attack which he was certain would come up too soon. He needed arms, men and time. He did not want to split up his forces by sending more men to the Alamo. Nor did he want the Mexicans to seize the cannon there for their own use or use the Alamo as a fort. For these reasons he gave orders to move the cannon to Gonzales and to destroy the Alamo. But the orders were never carried out. Colonel James Bowie delivered Houston's message to Colonel William B. Travis. Travis, the Alamo commander, did not obey these orders, but pleaded for more men. It was his firm belief that Santa Anna could be stopped at San Antonio, the first important settlement in Texas north of the Rio Grande River and Mexico. Even if they were defeated, he reasoned that the Mexicans would be delayed long enough for Houston to muster and train more men. Bowie agreed with him and stayed on at the Alamo.

Texas had so recently been opened up to Americans that everyone, it seemed, was a newcomer. Reputations were quickly established. Maverick had already proved his loyalty to the Texan cause and his qualities of leadership in the battle to retake San Antonio from General Cos. The men of San Antonio recognized in the slender young lawyer qualities of courage and intelligence, and they elected him in February, 1836, to represent them in the convention. This convention had been called to decide if Texas were to remain an independent state, faithful to the Mexican government under the constitution of 1824, or if it were to declare itself a free and sovereign nation.

Sam Maverick might well have been among his new friends who died as heroes in the battle of the Alamo. It was not lack of courage or a desire to avoid fighting which took him from the tragic scene. Travelling on horseback was a slow process and the convention in Washington-on-the-Brazos, one hundred and fifty miles away, had been called for March 1. Maverick had already started for the convention when the Mexican troops were sighted.

The Texans had heard that the Mexican army, commanded by Santa Anna himself, was on the move; but they did not realize how quickly it was approaching. The lookout sighted Mexican troops on February 23, 1836. Quickly the little band of one hundred and eighty-three men fortified themselves behind the walls of the Alamo and the siege began.