Historians of early Anglo settlement in Texas often face a key question regarding life on the frontier: to what extent did immigrants adapt to their new environments, and to what extent did they alter the new environment to resemble the old? The look of early Texas dwellings was certainly affected by the availability of various materials, leading to houses made of adobe, wood, brick, or stone. But the way in which those materials were used says volumes not only about the cultural backgrounds of those settlers but also about the rich variety that could be found in any one family's cultural baggage.

In thirty-two years of married life Samuel Augustus Maverick and his wife Mary Adams Maverick lived in seven houses. This strikingly high number is due in part to the fact that the Mavericks rented two houses early in their San Antonio residence, purchased a third, built two houses elsewhere in Texas, and rented one more house in San Antonio while building their final residence.

In their early years in San Antonio they adapted their houses to the local architectural vernacular (which was, of course, Hispanic), but later built a log cabin, then a raised cottage before building a house that recalled Sam's native South Carolina, a house situated in the very shadow of the former Spanish mission known as the Alamo.

And while the house types in which they lived were either Hispanic or Anglo, the hands that built some of those houses belonged to African Texans and German Texans. Although none of the Mavericks' houses survive, the memoirs of Mary Adams Maverick, combined with documentation of the structures, gives us unusually good data as to how one Texas family adopted and modified several Texas vernacular traditions before building a house form that was deeply rooted in Sam's youth.

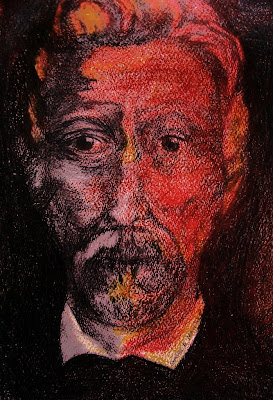

To understand the cultural environment of San Antonio in the 1830s and 1840s, it is necessary to delineate the roots of Sam and Mary Maverick in the American South and Sam's role in the Texas Revolution. Samuel Augustus Maverick was born in 1803 in the Pendleton District of South Carolina, in the far western part of the state. Though Pendleton was a raw, recently settled area, the elder Maverick was a Charleston merchant. Young Maverick lived both in urban Charleston and in the country at Pendleton until 1810, when the family permanently located to the latter location. Young Sam attended Yale, graduating in 1825, and subsequently studied law in Winchester, Virginia. Returning to South Carolina, he became involved in politics, but, as an opponent of John C. Calhoun's view that the states had the right to nullify any national law, Maverick realized that his chances of political advancement in his native state were remote. After briefly settling in southern Alabama, he decided to explore the possibility of moving to Texas. He entered Texas for the first time in April 1835, and arrived in San Antonio that September.

When Sam Maverick arrived in San Antonio in the fall of 1835, he found a town that was the most populous in Spanish Texas. It was defined by the mission of San Antonio de Valero on the east side of the San Antonio River and the Presidio of San Antonio de Bexar on the west side. The presidio created what became known as the Military Plaza, which by 1749 included the house of the commander of the presidio.

After an influx of settlers from the Canary Islands in 1731, the Main Plaza was laid out just to the east of the Military Plaza; with the construction of a parish church, San Fernando, the area on the west side of the river was often called the villa of San Fernando de Bexar.

Though four other missions were founded downriver, San Antonio remained centered on its three plazas.

In the fall of 1835 Anglo American colonizers were concluding that the repressive measures of Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna could be opposed only through armed conflict. One month later Mexican Gen. Martín Perfecto de Cós arrived with troops, determined that Bexar should remain a part of Mexico. Both the presidio and the Alamo mission were quickly fortified by Mexican troops. Maverick found himself placed under house arrest, but was freed in time to fight in the house-to-house combat that was the culmination of the siege of Bexar. Maverick was present when Ben Milam, the commander of the Texian forces, was shot and killed at the Veramendi house, just north of the Main Plaza.

The revolutionaries, who included both Anglos and Mexicans, forced Cós to surrender and retreat to the south.

The Texians secured the now-abandoned Alamo, and the talk of the town turned to the election of delegates to the convention to declare independence and draw up a constitution, which was to be held at Washington-on-the-Brazos. The residents of San Antonio—almost entirely Mexican—refused to allow the Alamo defenders to vote, considering these transients rather than residents. The Texians at the Alamo responded by holding their own election on February 1, 1836, and chose Sam Maverick as one of two delegates to represent them. Later that month Gen. Santa Anna arrived with his own forces and those of General Cós, and laid siege to the Alamo. Maverick remained at the Alamo until March 1, and did not arrive at Washington until after the vote for independence had been taken. He was in Washington, however, when word arrived that Santa Anna's troops had overrun the garrison on March 6, killing all 187 defenders. Maverick remained there until the independence convention had finished its business, then returned to Alabama to take care of his own affairs.

In Tuscaloosa Sam Maverick met Mary Ann Adams. Mary must have had a refined air about her, as Tuscaloosa was then the capital of Alabama, as well as home of the University of Alabama, which opened in 1831. The town was graced by a number of neoclassical buildings designed by the state architect, English-born William Nichols, including the capitol, the university, and Christ Episcopal Church, of which Mary was a member. Sam and Mary quickly fell in love, and they were married in the summer of 1836. After visiting with family in Alabama and South Carolina, the Mavericks returned to Texas at the beginning of 1838.

The Mavericks moved to Texas with an entourage of enslaved servants. From the Maverick side came Wiley, who drove the wagon; Jinny Anderson, a cook and Maverick's former nurse; and Jinny's four children. Mary's mother, Agatha Adams, gave her daughter three slaves: Rachel, a nurse, and Griffin and Granville, adult males. In 1845 Samuel would purchase four more African Americans for use as slaves. Frances and her son Simon, Nora, a seamstress; and William, a carpenter. The Mavericks owned more slaves than the typical Bejareño slaveholder: in 1850, when there were only 389 enslaved African Americans in Bexar County, they owned two adult males and eight females; by 1860, when the number of slaves in the county had increased to 1,395, they owned two males and sixteen females. Most slaveholders in the county owned five or fewer slaves. The Maverick family's ownership of nearly twenty slaves was one of the clearest indications that they represented the values—and vices—of the American South.

The first San Antonio house of Sam and Mary Maverick was rented from Don Jose Cassiano, who owned a house on the west side of the Main Plaza, with the Church of San Fernando to the north and Dolorosa Street to the south.

The house ran halfway back to the Military Plaza. Don Jose was renting the front room of this house to Mary's brother William Adams, for use as a store, and he offered to let the Mavericks live in the back while getting settled. The Mavericks spent about two and a half months in the house, from their arrival on June 15, 1838, until the first of September. At that point they rented a house on Soledad Street from the Huizar family.

Mary noted in her memoirs that these Huizars were descended from Pedro Huizar, who had crafted the portals of the San José Mission. The house was just north of the Veramendi house, which had been the scene of Maverick's service in the siege of Bexar. Though the Mavericks made no notable changes to either house, their choice of two dwellings either on or near the Main Plaza is evidence that they preferred their residence to be in the center of a bustling town rather than to be secluded in a suburb.

In January 1839 Sam Maverick was elected to a one-year term as mayor of San Antonio, beginning a political career that would also include service as an alderman and as a representative in the Texas legislature. In that same month he purchased the old Barrera place at Soledad and Commerce streets, at the northwest corner of Main Plaza.

This was the first house in San Antonio that the family owned, and here they began to make improvements.

Mary Maverick recalled that the main house was of stone and had three rooms, plus a shed attached on the east side of the northernmost room. The room at the corner of Houston and San Antonio, closest to the Main Plaza, had doors opening onto both streets. This Mary referred to as "the store-room," but Sam probably used this as his land office, the home base for his far-flung real estate empire. North of this was a "long room," in Mary's phrase, a longer, rectangular space. North of this was what Mary called the north room, which was most likely a dining room. The shed was east of this room, toward the river. The house backed up to a bend in the San Antonio River, shaded by "a grand old cypress" growing at the De la Zerda place next door.

Sam and Mary made significant changes to their new old house. They reinforced the shed with new adobe walls and divided it into a kitchen and a servant's room. They built an additional servant's room fronting on Soledad Street, separated from the main house by a gateway, or "zaguan." This echoed the zaguan of the Veramendi house just up the street, and like the Veramendi zaguan it probably had a smaller door for pedestrians set within the frame of the larger door for horses and wagons.

The presence of a long room marked the Barrera house as an elite residence. As Mary noted, "all considerable houses had a long-room for receptions." Theodore Gentilz's painting Fandango: Spanish Dance documents such a space. Though it has been claimed that the painting depicts the long room in the house of the presidio captain, now known as the Spanish Governor's Palace, the scene could have been in any number of elite houses in town, including the nearby Veramendi house. (The long room in the "Governor's Palace" is the only long room still extant.) The Mavericks divided their long room into two rooms, probably a parlor and a bedchamber. The partition was a brick wall with a fireplace, decorated with a mantelpiece.

In their remodeling, the Mavericks created an amalgam of Spanish and Anglo tendencies. Their use of adobe as a building material and their use of a zaguan gateway as the principal work entry showed considerable willingness to adapt to the local vernacular. Of course, their choice was the vernacular of the Mexican upper class: they did not purchase a rude jacal consisting of stakes driven into the ground, but a solid stone house with a long room. While the Mavericks could subdivide old rooms and add new ones, they could not change the linear nature of the rooms; there was no central passage to act as a receiving area, as had been the case in Anglo American houses for nearly a century. The rooms were invariably open to friends, family, and slaves.

The domain of the family's enslaved servants stretched from the north end of the property on Soledad Street to the kitchen, the yard, and the river. The zaguan led from Soledad Street into the yard, near which the Mavericks built a stable. One servant's room fronted Soledad Street on the north side of the zaguan, the other was deeper in the complex, beyond the kitchen. The two rooms housing enslaved servants may have reflected gender distinctions. The room off the kitchen was probably reserved for the female slaves: Jinny, the Maverick cook, her four children, and Rachel, the Maverick nursemaid. It seems most likely that Jinny asserted her authority over this room, the kitchen, and the adjacent yard. The room north of the zaguan was probably occupied by the male slaves Griffin and Granville. The arrangement seems unusual compared to arrangements in other urban slaveholding establishments in that the Mavericks did not block their slaves' access to the street; indeed, the male slaves' room may have served as something of a guard house.

The yard was entirely reserved for the slaves and their work: while such activities took place in the northern part of the yard, the southern part—with gardens and the bath house—was reserved for the family. These two parts of the yard were separated by "a strong but homely picket fence." This separation must have broken down on a weekly basis, however, as the bath house was also the place where the laundry was done. As more businesses opened up on the north side of Commerce Street, however, privacy for bathing diminished, and the Mavericks and other Anglo families took to bathing in more secluded stretches of the river.

The perception of space in the Barrera-Maverick house is nowhere better appreciated than in Mary's description of what she latter termed "A Day of Horrors." This was March 19, 1840, when sixty-five Comanches were in San Antonio to negotiate the release of hostages, a parley that went terribly wrong. Mary watched the proceedings from the yard of her friend, Mrs. Thomas Higginbotham, who lived across Commerce Street from the Mavericks and just north of the courthouse. Suddenly a "deafening war-whoop sounded in the Court room," and the Comanches drew their arrows and fired, killing both the county judge and the sheriff; San Antonians returned fire with their rifles. Mary and Mrs. Higginbotham ran into the latter's house. Mary did not stop but headed straight through the house and across Commerce to her own door. "Two Indians ran past me on the street and one reached my door as I got in. He turned to raise his hand to push it just as I beat down the heavy bar; then he ran on." Mary rushed on to the north room only to find Sam and her brother Andrew sitting at a table studying some survey plats. They had not heard a thing. She quickly informed them and dashed into the yard looking for her children, shouting, "Here are Indians! Here are Indians!" This was quite accurate, as three Comanches had entered through the zaguan and were making for the river. Jinny, the Maverick's enslaved cook, "stood bravely in front of the children, mine and hers, and I heard her cry out to the Indian, 'If you don't go 'way from here I'll mash your head with this rock!'" Mary recalled that "the Indian seemed regretful that he hadn't time to dispatch Jinny and her brood, but his time was short, and . . . he dash down the bank into the river." With her children safely inside, Mary watched from the Soledad Street door, and even wandered out into the street, even though the fight was far from over, and five Comanches lay dead in Commerce Street. "I was just twenty-two then," she recalled, "and was endowed with a fair share of curiosity."

Away from San Antonio the family built in a very different manner. In 1842, the reinstated General Santa Anna once again invaded Texas, causing many Texans to flee San Antonio. In March, Sam, Mary, their three children, and their slaves removed to Fayette County, just across the Colorado River from the county seat, La Grange. Sam almost immediately returned to San Antonio. He was taken captive by Mexican troops and marched to Mexico, where he was imprisoned until April 1843. Two of the family's enslaved servants, Granville and Wiley, built the Maverick's new house with assistance from a local man, Griffith Jones. Mary Maverick remembered the dwelling as "a log cabin of one room sixteen by eighteen feet, one smaller for a kitchen, and a shed room for Jinny and the children." The next year the Maverick's enslaved craftsmen enlarged the house with help from Mary's brother William, who was visiting from Alabama. This was "another log cabin, adjacent to the one previously built, leaving a passage or a hall between them. In this hall we usually sat when the weather was fair." Such log houses were the predominant housing form for pioneering Texans in the 1830s and 1840s.

That enslaved African Americans Granville and Wiley built the Mavericks' log cabin was not unusual for antebellum Texas, for enslaved artisans were employed on many building projects. In Austin the master builder, Abner Cook, used enslaved artisans to help construct the new State Capitol and the Governor's Mansion. Indeed, Frederick Law Olmsted noted that some slaveholders in Austin rented out their servants to work on the Capitol building. The brick walls of Ashton Villa in Galveston were laid by Aleck, a trained mason who was owned by the merchant James Moreau Brown. And African American slave craftsmen were responsible for many log houses and cabins.

Mary's recollection that the initial log house measured sixteen by eighteen feet corresponds exactly with what Terry Jordan characterized as a square or roughly square floor plan (as opposed to rectangular or elongated). The roughly square plan was the predominant type in that state. Mary's use of the term log cabin rather than log house suggests that the logs were left round and that they were, in Jordan's phrase, "crudely notched and projecting beyond the corners." Such cabins were widely viewed as impermanent houses, to be replaced by hewn log houses. If such cabins survived, they were used to house slaves.

Mary Maverick clearly indicated that the construction of the house was incremental. Even though the main house was just one room, the kitchen and living quarters for servants were separate. In this the Mavericks and their enslaved craftsmen followed long-standing Southern tradition. She also made clear that the development of the double pen with a central passage was a response to the Texas heat. Such an open passage or dog trot, growing out of a standard eighteenth-century Georgian-era plan, could be found across the lower South from Georgia to East Texas. Mary did not use the term dog-trot, but she did emphasize its use as a space for living in warm weather.

Mary also noted that her brother built in the passage "a settee or lounge with curtain frame around it; and this was intended for gentleman visitors who should remain all night." This may well reflect a desire to provide accommodation to travelers, though Mary seems to be saying that it would be occupied by those who were already visiting, and not simply strangers in need of a bed. The provision of a bed for gentlemen also speaks to the important issue of safety: Mary, her children, and the slaves lived most of the time there without Sam Maverick. A curtained settee for male visitors encouraged them to stay overnight, yet it was a space separate from the family's own space. The settee thus neatly balanced the safety of the family with concerns for propriety.

In 1845, the year in which the Republic of Texas agreed to join the United States, the Maverick family moved to Decrow's Point, near Matagorda, on the Gulf of Mexico. Maverick had made substantial investments in land there and apparently hoped to build a number of houses. While on a business trip to Charleston in December 1845 he bought four additional African Americans to use as slaves, including William, a twenty-four-year-old carpenter. Sam seems to have purchased William with the idea that he might provide much of the skilled labor needed to build houses at Decrow's. William proved to be unruly and uncooperative, however, and he was sent to New Orleans to be sold.

In the first four months of 1847, as the United States Army fought Santa Anna in the Mexican-American War, the Mavericks built a new house on the Gulf of Mexico at Decrow's Point. Mary noted that they built the kitchen and other outbuildings first and lived in those while the main house was under construction. Presumably William, the Maverick's enslaved carpenter, did much of the work on this house before he was sold. Sam Maverick also worked on the house, to his detriment: on March 19 he tripped on a loose step, fell twelve feet, and landed on his shoulder. He was incapacitated for close to three weeks. Their house was built of wood, three stories tall, with eight rooms. Mary wrote that "it was very roomy and commanded a fine view of both the bay and the gulf . . . so we all enjoyed greatly the new, clean cool, roomy house."

That the house was three stories tall suggested that it was a raised cottage with utility rooms below and the principal rooms above. It was most likely similar to the early houses of elites in Galveston, Texas, such as the Samuel May Williams House, which were adaptations of Creole house forms common along the Gulf Coast.

Originally the Williams House rested on ten-foot-high brick piers; the principal floor had a parlor, sitting room, and dining room, and five bedrooms were fitted under the steeply pitched hipped roof. Mary recalled that their house was "very substantially built, and calculated to resist a very considerable storm." Indeed, the Texas coast had been struck by a hurricane in October 1837. Mary recalled that they "were aware great storms might come and destructive cyclones at equinoxal times, and we often talked of going back to San Antonio." Though Mary loved the house on the coast, Sam's land dealings tied him ever more closely to San Antonio and West Texas, and the family left for Bexar in October of 1847.

The Mavericks still owned their house at the northeast corner of the Main Plaza, but Mary noted that the town did not seem as healthy as it had in the early forties. She wrote that "I felt that I could not live any longer at the old place, and Mr. Maverick, too did not want to live there. We concluded that the high ground on the Alamo Plaza would be a more healthful location." San Antonio had suffered through a cholera epidemic in 1849, which took the life of Sam and Mary's six-year-old daughter Augusta. This came just a year after the death of seven-year-old Agatha, so the old house was not only in the most crowded part of town but also held painful memories of the deaths of two of their children.

The Mavericks may also have been motivated to move because of the run-down appearance of their old house, in spite of an ever-increasing fortune that would have allowed them to build a new one. Mary's sister Lizzie teased her, "I understand that you are having a new house built. I am very glad to hear it for I am tired of being so often told of the old ruins in which you live." She reminded her sister that people remarked, "I wonder why Mr. Maverick doesn't live in a better house." Sam had gained a reputation not only for great wealth but also for frugality to the point of eccentricity; a new house would be more appropriate for a family of their wealth and stature.

Perhaps another issue was that while Sam and Mary had cordial relations with the Mexican elite of San Antonio, they were not close friends. Mary noted that while they exchanged calls with leading families such as the Navarros, Seguins, Veramindis, and Yturris, she "never felt like being at all intimate." She did not want the children to spend much time with the children of the Mexican elites "because they let theirs go almost naked." Mary thus sketched out the gulf between the mores of Victorian-era Anglos and Mexicans. And given that these families all lived on or near the Main Plaza, the Mavericks were apparently not disturbed at the thought of moving farther away.

The family moved in July 1849 from the Main Plaza to the Alamo Plaza. Sam had acquired land near the old mission church and convento, at the northwestern edge of the plaza in 1841. Between 1844 and 1849 he bought four large parcels of land between the Alamo Plaza and the San Antonio River. At first the family occupied "an old Mexican house" on the west side of the plaza and on the south side of what would become Houston Street, across from the site where they would build their new house.

Indeed, this house probably incorporated a room (or rooms) from the west wall of the mission enclosure, which had served one hundred years before as apartments for Indian converts. It was bounded on the north and west by the Alamo acequia, which was by then abandoned. The Mavericks would spend nearly a year and a half in this house, as work did not begin on the new house until June 1850, and they did not move in until the first of December. Mary did not note any changes the family made to the house; perhaps all their energy went into planning the new structure. Indeed, her only comment about their latest temporary abode was made in connection with the new house, which they found "very nice, after the old Mexican quarters we had occupied for over a year."

The neighborhood into which they moved was not only predominantly Mexican but also predominantly poor. When Frederick Law Olmsted visited town in 1854, he found the Alamo "a mere wreck of its former grandeur," and in use as an arsenal by the U.S. Quartermaster. He described the Alamo Plaza as "all Mexican. Windowless cabins of stakes, plastered with mud and roofed with river-grass, or 'tula'; or low, windowless, but better thatched, houses of adobes (gray, unburnt bricks), with groups of brown idlers lounging at their doors." Interestingly, Olmsted chose not to mention the Maverick House, sitting prominently at the northwest corner of the plaza.

Sam and Mary Maverick moved with an awareness that things were changing on the Alamo Plaza, however. In 1849 the U.S. Department of War named San Antonio headquarters for all army operations in Texas, and on January 1, 1850, Jean Marie Odin, the Catholic Bishop of Texas, agreed to rent the entire Alamo compound to the army for $150 per month. Maj. Edwin Burr Babbitt, the chief quartermaster for San Antonio, recommended to Gen. Thomas S. Jessup that the Alamo buildings be demolished and new ones erected, but Jessup overruled this suggestion. In the spring of 1850 Babbitt reroofed the mission church, adding a second floor and a curvilinear parapet. Maverick also rented an adjacent lot to the army for $20 per month. The mission church was used for the rather mundane purpose of storing foodstuffs, but the army's occupancy meant that the building would not deteriorate any further. Others also saw the eastern side of town as ripe for redevelopment: in 1859 John Fries and J.H. Kampmann began to build a large new hotel, to be known as the Menger Hotel, just south of the Alamo. In that same year, Sam Maverick acquired another large parcel of land northwest of Alamo Plaza; from this land the Mavericks would eventually donate Travis Park to the city, and, on the north side of the park, the site for St. Mark's Episcopal Church.

Ultimately, though, the selection of Alamo Plaza as the site for the Maverick House was a very personal one for Sam Maverick. In an 1846 letter to Mary, Sam referred to the Alamo as "the old Golgotha." This Aramaic word for skull denotes the hill where Jesus Christ was crucified, known in its Latin form as Calvary. In more modern times Golgotha had taken on the connotations of a graveyard or charnel house. Maverick thus remained intensely aware of the human sacrifice that had taken place on that spot little more than a decade earlier and may have been using the term not only in its generic sense, but also to draw an analogy between the sacrifice of the Alamo defenders and Christ himself. The next year he wrote to S.M. Howe, a U.S. Army officer in San Antonio, "I have a desire to reside on this particular spot, a foolish prejudice no doubt as I was almost a solitary escape[e] from the Alamo massacre having been sent by those unfortunate men [to the independence convention]." If Sam and Mary had their bedchamber in the south room upstairs, they may well have had a remarkable view of the old mission that had played such a memorable role in their own lives and in the history of their state.

An 1877 photograph shows that the Maverick House was a two-story block with the gables at the north and south end and a two-story gallery on the west side. The south wall had one window on each floor, and the longer west side had three per floor. The roof began several feet above the lintels of the second floor window, suggesting that the attic contained usable space. No dormers were visible, but the gable end has what appears to be a ventilator. The narrowness of the chimney suggests that it served cast-iron stoves rather than traditional fireplaces. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of 1885 and 1888, when the property had become a boardinghouse, make sense of the outbuildings visible in the photograph and document features not visible in the photograph.

The two-story gallery was actually L-shaped, attaching the main block of the house to a two-story kitchen. Connecting the main house and kitchen with a gallery was fairly typical in larger houses in Texas and, indeed, elsewhere in the South, but less typical was the fact that the kitchen was not situated behind the main house, but to the north and west of the main block. The longer south façade of the kitchen looked toward Houston Street, so that the main block and kitchen formed a courtyard.

The second floor of the kitchen may have housed some of the Mavericks' enslaved servants, but it could also have been separate living quarters for the older Maverick boys. Samuel was thirteen in 1850 and Lewis was eleven, though at five and three George and William were rather young to be apart from their parents. Whatever the function of the upper room of the kitchen block, the Sanborn Maps also indicate the presence of a one-story building north of the main house, with a south-facing front porch and a connector to the main house. This northernmost building may have housed the male slaves, just as room north of the zaguan had housed them in the old house on Main Plaza. Even in the 1880s, when the property was a boardinghouse, this building was labeled as a "servant's room." The Sanborn Maps cannot tell us whether either the kitchen or the servant's room date to 1850, but both are visible in an 1873 bird's-eye view of the city.

By this time, Sam had passed away but Mary was living there; clearly these outbuildings had been there for some time.

A final outbuilding is known through both the photograph and the Sanborn Maps: the Maverick Land Office. This was a low-roofed one-story building with front and back rooms, both lit by eastern windows. The door opened directly onto Houston Street, meaning that visitors to the land office did not have to enter the yard of the house. At the old house on the Main Plaza, the office was in the main block of the house nearest the plaza, but here the commercial aspects of the complex were strictly separated from the residential.

The Sanborn Maps also reveal that most of the buildings in the Maverick compound were made of stone: the main house, kitchen, servant's room, and land office. The only frame structures were two small outbuildings, one west of the kitchen and another west of the servant's room. The use of stone was traditional in important San Antonio buildings, such as the eighteenth-century missions and the residence of the presidio commander, though poorer folk lived in one-room jacales, with walls of wooden posts driven into the ground.

The form of the Maverick House was highly unusual for an Anglo family in San Antonio. The house of John James, a business partner of Maverick's, was a far more typical Anglo Texan house. James's main house was a squarish block set back from the street, with galleries on both the front and rear elevations; the kitchen, a separate building behind the main house, had only a front gallery. Both the first floor of the main house and the kitchen were built of stone; later Sanborn Maps show a frame second floor to the main house, which may have been a later addition. Both the way in which the James House related to the street and the relation between house and kitchen marked it as being more conventionally Anglo Texan.

An even more imposing Anglo Texan house was that of James Vance, a New York-born merchant and banker. This house, built south of the Main Plaza, was two stories high and had a partially submerged basement. Both the principal front, facing in the direction of the plaza, and the rear elevation had colonnades with Greek Revival box columns. A central passage with a staircase ran through the house on the ground floor and the upper two floors. The entire house was built of stone, and family tradition claims that the architect builder was John Fries, a German stonemason. Olmsted observed that "the American dwellings stand back, with galleries and jalousies and a garden picket fence against the walk," which could describe the James, Vance, or Maverick houses.

The Maverick house in San Antonio was also different from that designed by relatives back in South Carolina. Montpelier, Sam's father's house in Pendleton, in the western part of the state, burned early in 1850. The senior Maverick had recently suffered a stroke, and so the task of rebuilding fell to his son-in-law William Van Wyck. The new house, built a short distance from the old one, featured a central passage and four rooms downstairs and up, a plan characteristic of many Greek Revival, Federal, and Georgian houses. Four square piers create a two-story central portico; more unusual was the cast-iron balcony to the right of the entrance portico, which opened into the drawing room. Although the Maverick-Van Wyck house was some 245 miles inland from Charleston, it featured a typical central passage plan and fashionable neoclassical ornament.

The Maverick house was unlike other Anglo Texan houses in San Antonio or the house of Sam's brother-in-law in South Carolina; however, the house possessed a number of characteristics associated with the house form known as the Charleston single house.

This form developed in Charleston, South Carolina, in the mid-eighteenth century. The simplest definition is a house with only one room fronting the street. By the latter eighteenth century, single houses would have a two-story gallery, preferably facing south. Any garden would be in front of this gallery, and the main entrance would be on the center of this façade. In plan the house would have a central passage with a room on each side, and it would have two or three stories. Often the long wall opposite the gallery would have the fireplaces and no windows, almost as if it were expected that another house was to be built adjoining that wall. Usually the kitchen, laundry, and slave quarters would be placed to the rear of the property.

The Maverick house showed a single room to Houston Street, with a gallery on the side. A letter from Mary to her son Lewis in 1863 provides evidence that there were in fact three rooms downstairs, a fact supported by the three equal-sized windows in the surviving photograph. She specifies that these rooms were the north room, the dining room, and the sitting room. The absence of an entrance hall or stair hall is significant. Central passages were common in eighteenth-century houses in the eastern states; a design that scholars refer to as the Georgian plan. Even Charleston single houses had central passages, albeit opening onto the garden rather than the street. The Maverick family's arrangement of three downstairs rooms is actually much closer to Creole floor plans of Louisiana. And indeed houses like the Major James Pitot House in New Orleans (built 1799-1805) feature a dining room as the central room on the ground floor. The lack of a stair hall suggests that the main access to the upstairs was from a stair on the gallery, as was the case in such major Louisiana houses of the 1830s as the David Weeks Home, now known as Shadows-on-the-Teche. The Weeks house, having six rooms on each floor is not a single house, but single houses in New Orleans have a gallery on the side and two or three rooms on each floor.

The Maverick house had gardens and a majestic pecan tree—under which Sam Maverick was said to have camped on his first night in San Antonio—just west of the gallery. The kitchen faced the gardens on the north; the slave house was less visible, being directly north of the big house. The house also relates more specifically to the antebellum-era single house, in that the roof was gabled rather than hipped, and two stories rather than three. The principal difference from the typical single house were that the house was set back from the street on the south and east sides, and the fireplaces were most likely not on the long wall opposite the gallery. The wall opposite the gallery had three windows per floor, but this could also be the case in Charleston single houses on corner lots. The Mavericks' lot was in fact a corner lot and would have no near neighbors. Indeed, it might be seen as a suburbanized single house.

The single house was a form with which Sam Maverick was familiar from his youth, and, indeed, he had spent a great deal of time in Charleston as recently as 1845. A few single houses could also be found in Alabama, but these were all in Mobile, on the Gulf Coast, rather than in Mary Maverick's Tuscaloosa. She would have been far more familiar with houses with a central passage, either in their one- or two-story versions. Between Sam and Mary, Sam seems the more likely source for such a plan.

If the plan for a Charleston single house did not come from Sam Maverick, it may have come from Francois Pierre Giraud, who was born in Charleston of French parents. He attended St. Mary's College prep school in Maryland then traveled to France to study at the Ecole Centrale des Arts et Manufactures. He was back in the United States by 1842 and came to the new state of Texas in 1847. He became the first city surveyor of San Antonio in 1848 and determined the boundaries of the city and of the mission properties. In fact, Sam Maverick conferred with Giraud about the precise bounds of the mission land at the northwest corner to make sure of his title to the property. During the Civil War, Giraud was chief engineer of defenses at Galveston and served as San Antonio's mayor from 1872 to 1875. His architectural work included the Ursuline Academy, built in phases from 1849 to 1868, and the new San Fernando Cathedral, built between 1868 and 1873 in an austere Gothic style. Although no other houses by Giraud are known, he was certainly capable of obliging his fellow South Carolinian with such a design.

It is less likely that the form of the house was determined by the contractors who built it. The stonework was done by Joseph Schmidt, a German-born mason, and the woodwork by Otto Bombach, a German-born carpenter. Mary noted that Schmidt "pushed the work rapidly" on the Maverick house. Thus both the stonework and woodwork of the Maverick House were thus erected by a group of recent immigrants from Germany, who would have had little familiarity with the single house form.

The single house has been interpreted as an environmental response to heat and humidity and as a response to limited land on which to build in Charleston. Both of these interpretations leave much to be desired. Although the galleries shaded the house from the direct glare of the sun and provided a place where one could catch a cool breeze, the windowless walls abutting the next property were hardly conducive to the circulation of air. And though land may have been a scarce commodity in Charleston, many of the single houses were in fact showy in setting aside space for gardens and other amenities. More recently, Bernard Herman has argued that the single house form was essentially an urban plantation and a tool for social control. Genteel social functions were grouped at the front, while work functions and slave housing were grouped at the rear.

The galleries of the Maverick house can certainly be seen as providing cool and shady spaces in an attempt to cope with the Texas heat, but at the same time other Texas houses had galleries front and back; environment does not explain why the Mavericks chose this arrangement of galleries over more typical Texas arrangements. Nor was lack of land on which to build an issue for the Mavericks: they had sufficient space on their lot to set the house back from Houston Street and D Street. But the arrangement of the Maverick complex does suggest its effectiveness in defining types of space: they made a clear distinction between the rear yard and the front and side yard. The rear yard was defined by the north wall of the big house, the east wall of the kitchen, the south front of the slave house, and the fence separating the yard from D Street. At the same time the placement of the servant house at the north end of the property along D Street made it easy for Maverick slaves to have access to the outside world. Nearer the main house the continuation of the gallery along the front of the kitchen created a shady and more genteel space that also screened the view of the kitchen from the garden and from Houston Street. Although the complex was bounded by a picket fence, it is likely that the daily duties of the Maverick slaves made this a very porous barrier.

The Mavericks continued to live on the Alamo Plaza until Sam's death in 1870. Over time the once-new house began to take on a ramshackle appearance. A somewhat acerbic newspaper article of 1868, reporting his purchase of some 1,650 acres of land, noted that "Maverick lives in the most simple style—fences decaying and buildings crumbling to pieces; yet he is eternally buying land." The house was not yet twenty years old, but its maintenance did not seem to be a high priority for Sam.

Mary continued to live in the house for nearly a decade after Sam's death, but the neighborhood was beginning to change. By the time Augustus Koch did his bird's-eye view of San Antonio in 1873, a two-story grocery store had been built north of the Maverick house, although the block to the west of the Maverick complex was still vacant. In 1877 the U.S. Army moved out of the Alamo complex for the new quarters at Post San Antonio (now known as Fort Sam Houston). The Catholic Church then sold the convento to the merchants Hugo and Schmeltzer, who converted the building into a wholesale liquor and grocery store. The merchants added a false parapet and wooden cannons in an attempt to capitalize on the Alamo's image.

By the time the 1879-1880 city directory appeared, Mary was living with her daughter Mary and her second husband, Edwin Terrell. Their house was on the south side of Travis Park, land that had been donated to the city by the Mavericks. The elder Mary would have found it convenient to stroll to the north side of the park to St. Mark's Episcopal Church, which she and Sam had helped fund. The church was designed by Richard Upjohn of New York in 1859, but it was not completed and consecrated until 1881. Mary noted that "a feeling of local pride has been aroused, even among those who are not of us, that Old San Antonio, in wilderness as she is and almost out of the world as she is thought to be, should possess such a fine church."

She also served for many years as the president of the Alamo Monument Association, which advocated demolishing the liquor and grocery store next to the Alamo and constructing a large monument designed by the English-born Alfred Giles, the first professional architect in San Antonio. Mary's sons Albert and William also had Giles design a commercial building for the west side of Alamo Plaza. This was the Italianate Crockett Block (1882-1883), named for the hero of the battle of the Alamo. After the death of her daughter, Mary lived with her son William in a limestone Romanesque house (1893) designed by Giles. There she lived until her death in 1898.

The 1879-1880 city directory also indicated that James Moore was running a boardinghouse at the northwest corner of Houston and Avenue D, that is, the old Maverick House. The neighborhood had never been particularly residential, in spite of the Mavericks' example, but it was becoming less so all the time. In 1885 Sam and Mary's oldest son, also named Sam, founded the Maverick Bank and built a five-story building across Houston Street from the old house, on the site of the old Mexican house where they had lived for a year and a half. Unfortunately for Sam, the bank did not do well and was out of business by 1892. Across the street to the east the building that housed the U.S. courthouse, customhouse, and post office was completed in 1890—a large Victorian structure that also would have dwarfed the Mavericks' old house. The Maverick House was demolished sometime between 1890 and early 1892. It was replaced by a row of six offices on Houston Street—incorporating the old land office—and five on Avenue D. The Maverick House stood for less than fifty years, succumbing to the tremendous growth of late nineteenth-century San Antonio.

In thirty-two years of married life Samuel Augustus Maverick and his wife Mary Adams Maverick lived in seven houses. This strikingly high number is due in part to the fact that the Mavericks rented two houses early in their San Antonio residence, purchased a third, built two houses elsewhere in Texas, and rented one more house in San Antonio while building their final residence.

In their early years in San Antonio they adapted their houses to the local architectural vernacular (which was, of course, Hispanic), but later built a log cabin, then a raised cottage before building a house that recalled Sam's native South Carolina, a house situated in the very shadow of the former Spanish mission known as the Alamo.

And while the house types in which they lived were either Hispanic or Anglo, the hands that built some of those houses belonged to African Texans and German Texans. Although none of the Mavericks' houses survive, the memoirs of Mary Adams Maverick, combined with documentation of the structures, gives us unusually good data as to how one Texas family adopted and modified several Texas vernacular traditions before building a house form that was deeply rooted in Sam's youth.

To understand the cultural environment of San Antonio in the 1830s and 1840s, it is necessary to delineate the roots of Sam and Mary Maverick in the American South and Sam's role in the Texas Revolution. Samuel Augustus Maverick was born in 1803 in the Pendleton District of South Carolina, in the far western part of the state. Though Pendleton was a raw, recently settled area, the elder Maverick was a Charleston merchant. Young Maverick lived both in urban Charleston and in the country at Pendleton until 1810, when the family permanently located to the latter location. Young Sam attended Yale, graduating in 1825, and subsequently studied law in Winchester, Virginia. Returning to South Carolina, he became involved in politics, but, as an opponent of John C. Calhoun's view that the states had the right to nullify any national law, Maverick realized that his chances of political advancement in his native state were remote. After briefly settling in southern Alabama, he decided to explore the possibility of moving to Texas. He entered Texas for the first time in April 1835, and arrived in San Antonio that September.

When Sam Maverick arrived in San Antonio in the fall of 1835, he found a town that was the most populous in Spanish Texas. It was defined by the mission of San Antonio de Valero on the east side of the San Antonio River and the Presidio of San Antonio de Bexar on the west side. The presidio created what became known as the Military Plaza, which by 1749 included the house of the commander of the presidio.

After an influx of settlers from the Canary Islands in 1731, the Main Plaza was laid out just to the east of the Military Plaza; with the construction of a parish church, San Fernando, the area on the west side of the river was often called the villa of San Fernando de Bexar.

Though four other missions were founded downriver, San Antonio remained centered on its three plazas.

In the fall of 1835 Anglo American colonizers were concluding that the repressive measures of Mexican President Antonio López de Santa Anna could be opposed only through armed conflict. One month later Mexican Gen. Martín Perfecto de Cós arrived with troops, determined that Bexar should remain a part of Mexico. Both the presidio and the Alamo mission were quickly fortified by Mexican troops. Maverick found himself placed under house arrest, but was freed in time to fight in the house-to-house combat that was the culmination of the siege of Bexar. Maverick was present when Ben Milam, the commander of the Texian forces, was shot and killed at the Veramendi house, just north of the Main Plaza.

The revolutionaries, who included both Anglos and Mexicans, forced Cós to surrender and retreat to the south.

The Texians secured the now-abandoned Alamo, and the talk of the town turned to the election of delegates to the convention to declare independence and draw up a constitution, which was to be held at Washington-on-the-Brazos. The residents of San Antonio—almost entirely Mexican—refused to allow the Alamo defenders to vote, considering these transients rather than residents. The Texians at the Alamo responded by holding their own election on February 1, 1836, and chose Sam Maverick as one of two delegates to represent them. Later that month Gen. Santa Anna arrived with his own forces and those of General Cós, and laid siege to the Alamo. Maverick remained at the Alamo until March 1, and did not arrive at Washington until after the vote for independence had been taken. He was in Washington, however, when word arrived that Santa Anna's troops had overrun the garrison on March 6, killing all 187 defenders. Maverick remained there until the independence convention had finished its business, then returned to Alabama to take care of his own affairs.

In Tuscaloosa Sam Maverick met Mary Ann Adams. Mary must have had a refined air about her, as Tuscaloosa was then the capital of Alabama, as well as home of the University of Alabama, which opened in 1831. The town was graced by a number of neoclassical buildings designed by the state architect, English-born William Nichols, including the capitol, the university, and Christ Episcopal Church, of which Mary was a member. Sam and Mary quickly fell in love, and they were married in the summer of 1836. After visiting with family in Alabama and South Carolina, the Mavericks returned to Texas at the beginning of 1838.

The Mavericks moved to Texas with an entourage of enslaved servants. From the Maverick side came Wiley, who drove the wagon; Jinny Anderson, a cook and Maverick's former nurse; and Jinny's four children. Mary's mother, Agatha Adams, gave her daughter three slaves: Rachel, a nurse, and Griffin and Granville, adult males. In 1845 Samuel would purchase four more African Americans for use as slaves. Frances and her son Simon, Nora, a seamstress; and William, a carpenter. The Mavericks owned more slaves than the typical Bejareño slaveholder: in 1850, when there were only 389 enslaved African Americans in Bexar County, they owned two adult males and eight females; by 1860, when the number of slaves in the county had increased to 1,395, they owned two males and sixteen females. Most slaveholders in the county owned five or fewer slaves. The Maverick family's ownership of nearly twenty slaves was one of the clearest indications that they represented the values—and vices—of the American South.

The first San Antonio house of Sam and Mary Maverick was rented from Don Jose Cassiano, who owned a house on the west side of the Main Plaza, with the Church of San Fernando to the north and Dolorosa Street to the south.

The house ran halfway back to the Military Plaza. Don Jose was renting the front room of this house to Mary's brother William Adams, for use as a store, and he offered to let the Mavericks live in the back while getting settled. The Mavericks spent about two and a half months in the house, from their arrival on June 15, 1838, until the first of September. At that point they rented a house on Soledad Street from the Huizar family.

Mary noted in her memoirs that these Huizars were descended from Pedro Huizar, who had crafted the portals of the San José Mission. The house was just north of the Veramendi house, which had been the scene of Maverick's service in the siege of Bexar. Though the Mavericks made no notable changes to either house, their choice of two dwellings either on or near the Main Plaza is evidence that they preferred their residence to be in the center of a bustling town rather than to be secluded in a suburb.

In January 1839 Sam Maverick was elected to a one-year term as mayor of San Antonio, beginning a political career that would also include service as an alderman and as a representative in the Texas legislature. In that same month he purchased the old Barrera place at Soledad and Commerce streets, at the northwest corner of Main Plaza.

This was the first house in San Antonio that the family owned, and here they began to make improvements.

Mary Maverick recalled that the main house was of stone and had three rooms, plus a shed attached on the east side of the northernmost room. The room at the corner of Houston and San Antonio, closest to the Main Plaza, had doors opening onto both streets. This Mary referred to as "the store-room," but Sam probably used this as his land office, the home base for his far-flung real estate empire. North of this was a "long room," in Mary's phrase, a longer, rectangular space. North of this was what Mary called the north room, which was most likely a dining room. The shed was east of this room, toward the river. The house backed up to a bend in the San Antonio River, shaded by "a grand old cypress" growing at the De la Zerda place next door.

Sam and Mary made significant changes to their new old house. They reinforced the shed with new adobe walls and divided it into a kitchen and a servant's room. They built an additional servant's room fronting on Soledad Street, separated from the main house by a gateway, or "zaguan." This echoed the zaguan of the Veramendi house just up the street, and like the Veramendi zaguan it probably had a smaller door for pedestrians set within the frame of the larger door for horses and wagons.

The presence of a long room marked the Barrera house as an elite residence. As Mary noted, "all considerable houses had a long-room for receptions." Theodore Gentilz's painting Fandango: Spanish Dance documents such a space. Though it has been claimed that the painting depicts the long room in the house of the presidio captain, now known as the Spanish Governor's Palace, the scene could have been in any number of elite houses in town, including the nearby Veramendi house. (The long room in the "Governor's Palace" is the only long room still extant.) The Mavericks divided their long room into two rooms, probably a parlor and a bedchamber. The partition was a brick wall with a fireplace, decorated with a mantelpiece.

In their remodeling, the Mavericks created an amalgam of Spanish and Anglo tendencies. Their use of adobe as a building material and their use of a zaguan gateway as the principal work entry showed considerable willingness to adapt to the local vernacular. Of course, their choice was the vernacular of the Mexican upper class: they did not purchase a rude jacal consisting of stakes driven into the ground, but a solid stone house with a long room. While the Mavericks could subdivide old rooms and add new ones, they could not change the linear nature of the rooms; there was no central passage to act as a receiving area, as had been the case in Anglo American houses for nearly a century. The rooms were invariably open to friends, family, and slaves.

The domain of the family's enslaved servants stretched from the north end of the property on Soledad Street to the kitchen, the yard, and the river. The zaguan led from Soledad Street into the yard, near which the Mavericks built a stable. One servant's room fronted Soledad Street on the north side of the zaguan, the other was deeper in the complex, beyond the kitchen. The two rooms housing enslaved servants may have reflected gender distinctions. The room off the kitchen was probably reserved for the female slaves: Jinny, the Maverick cook, her four children, and Rachel, the Maverick nursemaid. It seems most likely that Jinny asserted her authority over this room, the kitchen, and the adjacent yard. The room north of the zaguan was probably occupied by the male slaves Griffin and Granville. The arrangement seems unusual compared to arrangements in other urban slaveholding establishments in that the Mavericks did not block their slaves' access to the street; indeed, the male slaves' room may have served as something of a guard house.

The yard was entirely reserved for the slaves and their work: while such activities took place in the northern part of the yard, the southern part—with gardens and the bath house—was reserved for the family. These two parts of the yard were separated by "a strong but homely picket fence." This separation must have broken down on a weekly basis, however, as the bath house was also the place where the laundry was done. As more businesses opened up on the north side of Commerce Street, however, privacy for bathing diminished, and the Mavericks and other Anglo families took to bathing in more secluded stretches of the river.

The perception of space in the Barrera-Maverick house is nowhere better appreciated than in Mary's description of what she latter termed "A Day of Horrors." This was March 19, 1840, when sixty-five Comanches were in San Antonio to negotiate the release of hostages, a parley that went terribly wrong. Mary watched the proceedings from the yard of her friend, Mrs. Thomas Higginbotham, who lived across Commerce Street from the Mavericks and just north of the courthouse. Suddenly a "deafening war-whoop sounded in the Court room," and the Comanches drew their arrows and fired, killing both the county judge and the sheriff; San Antonians returned fire with their rifles. Mary and Mrs. Higginbotham ran into the latter's house. Mary did not stop but headed straight through the house and across Commerce to her own door. "Two Indians ran past me on the street and one reached my door as I got in. He turned to raise his hand to push it just as I beat down the heavy bar; then he ran on." Mary rushed on to the north room only to find Sam and her brother Andrew sitting at a table studying some survey plats. They had not heard a thing. She quickly informed them and dashed into the yard looking for her children, shouting, "Here are Indians! Here are Indians!" This was quite accurate, as three Comanches had entered through the zaguan and were making for the river. Jinny, the Maverick's enslaved cook, "stood bravely in front of the children, mine and hers, and I heard her cry out to the Indian, 'If you don't go 'way from here I'll mash your head with this rock!'" Mary recalled that "the Indian seemed regretful that he hadn't time to dispatch Jinny and her brood, but his time was short, and . . . he dash down the bank into the river." With her children safely inside, Mary watched from the Soledad Street door, and even wandered out into the street, even though the fight was far from over, and five Comanches lay dead in Commerce Street. "I was just twenty-two then," she recalled, "and was endowed with a fair share of curiosity."

Away from San Antonio the family built in a very different manner. In 1842, the reinstated General Santa Anna once again invaded Texas, causing many Texans to flee San Antonio. In March, Sam, Mary, their three children, and their slaves removed to Fayette County, just across the Colorado River from the county seat, La Grange. Sam almost immediately returned to San Antonio. He was taken captive by Mexican troops and marched to Mexico, where he was imprisoned until April 1843. Two of the family's enslaved servants, Granville and Wiley, built the Maverick's new house with assistance from a local man, Griffith Jones. Mary Maverick remembered the dwelling as "a log cabin of one room sixteen by eighteen feet, one smaller for a kitchen, and a shed room for Jinny and the children." The next year the Maverick's enslaved craftsmen enlarged the house with help from Mary's brother William, who was visiting from Alabama. This was "another log cabin, adjacent to the one previously built, leaving a passage or a hall between them. In this hall we usually sat when the weather was fair." Such log houses were the predominant housing form for pioneering Texans in the 1830s and 1840s.

That enslaved African Americans Granville and Wiley built the Mavericks' log cabin was not unusual for antebellum Texas, for enslaved artisans were employed on many building projects. In Austin the master builder, Abner Cook, used enslaved artisans to help construct the new State Capitol and the Governor's Mansion. Indeed, Frederick Law Olmsted noted that some slaveholders in Austin rented out their servants to work on the Capitol building. The brick walls of Ashton Villa in Galveston were laid by Aleck, a trained mason who was owned by the merchant James Moreau Brown. And African American slave craftsmen were responsible for many log houses and cabins.

Mary's recollection that the initial log house measured sixteen by eighteen feet corresponds exactly with what Terry Jordan characterized as a square or roughly square floor plan (as opposed to rectangular or elongated). The roughly square plan was the predominant type in that state. Mary's use of the term log cabin rather than log house suggests that the logs were left round and that they were, in Jordan's phrase, "crudely notched and projecting beyond the corners." Such cabins were widely viewed as impermanent houses, to be replaced by hewn log houses. If such cabins survived, they were used to house slaves.

Mary Maverick clearly indicated that the construction of the house was incremental. Even though the main house was just one room, the kitchen and living quarters for servants were separate. In this the Mavericks and their enslaved craftsmen followed long-standing Southern tradition. She also made clear that the development of the double pen with a central passage was a response to the Texas heat. Such an open passage or dog trot, growing out of a standard eighteenth-century Georgian-era plan, could be found across the lower South from Georgia to East Texas. Mary did not use the term dog-trot, but she did emphasize its use as a space for living in warm weather.

Mary also noted that her brother built in the passage "a settee or lounge with curtain frame around it; and this was intended for gentleman visitors who should remain all night." This may well reflect a desire to provide accommodation to travelers, though Mary seems to be saying that it would be occupied by those who were already visiting, and not simply strangers in need of a bed. The provision of a bed for gentlemen also speaks to the important issue of safety: Mary, her children, and the slaves lived most of the time there without Sam Maverick. A curtained settee for male visitors encouraged them to stay overnight, yet it was a space separate from the family's own space. The settee thus neatly balanced the safety of the family with concerns for propriety.

In 1845, the year in which the Republic of Texas agreed to join the United States, the Maverick family moved to Decrow's Point, near Matagorda, on the Gulf of Mexico. Maverick had made substantial investments in land there and apparently hoped to build a number of houses. While on a business trip to Charleston in December 1845 he bought four additional African Americans to use as slaves, including William, a twenty-four-year-old carpenter. Sam seems to have purchased William with the idea that he might provide much of the skilled labor needed to build houses at Decrow's. William proved to be unruly and uncooperative, however, and he was sent to New Orleans to be sold.

In the first four months of 1847, as the United States Army fought Santa Anna in the Mexican-American War, the Mavericks built a new house on the Gulf of Mexico at Decrow's Point. Mary noted that they built the kitchen and other outbuildings first and lived in those while the main house was under construction. Presumably William, the Maverick's enslaved carpenter, did much of the work on this house before he was sold. Sam Maverick also worked on the house, to his detriment: on March 19 he tripped on a loose step, fell twelve feet, and landed on his shoulder. He was incapacitated for close to three weeks. Their house was built of wood, three stories tall, with eight rooms. Mary wrote that "it was very roomy and commanded a fine view of both the bay and the gulf . . . so we all enjoyed greatly the new, clean cool, roomy house."

That the house was three stories tall suggested that it was a raised cottage with utility rooms below and the principal rooms above. It was most likely similar to the early houses of elites in Galveston, Texas, such as the Samuel May Williams House, which were adaptations of Creole house forms common along the Gulf Coast.

Originally the Williams House rested on ten-foot-high brick piers; the principal floor had a parlor, sitting room, and dining room, and five bedrooms were fitted under the steeply pitched hipped roof. Mary recalled that their house was "very substantially built, and calculated to resist a very considerable storm." Indeed, the Texas coast had been struck by a hurricane in October 1837. Mary recalled that they "were aware great storms might come and destructive cyclones at equinoxal times, and we often talked of going back to San Antonio." Though Mary loved the house on the coast, Sam's land dealings tied him ever more closely to San Antonio and West Texas, and the family left for Bexar in October of 1847.

The Mavericks still owned their house at the northeast corner of the Main Plaza, but Mary noted that the town did not seem as healthy as it had in the early forties. She wrote that "I felt that I could not live any longer at the old place, and Mr. Maverick, too did not want to live there. We concluded that the high ground on the Alamo Plaza would be a more healthful location." San Antonio had suffered through a cholera epidemic in 1849, which took the life of Sam and Mary's six-year-old daughter Augusta. This came just a year after the death of seven-year-old Agatha, so the old house was not only in the most crowded part of town but also held painful memories of the deaths of two of their children.

The Mavericks may also have been motivated to move because of the run-down appearance of their old house, in spite of an ever-increasing fortune that would have allowed them to build a new one. Mary's sister Lizzie teased her, "I understand that you are having a new house built. I am very glad to hear it for I am tired of being so often told of the old ruins in which you live." She reminded her sister that people remarked, "I wonder why Mr. Maverick doesn't live in a better house." Sam had gained a reputation not only for great wealth but also for frugality to the point of eccentricity; a new house would be more appropriate for a family of their wealth and stature.

Perhaps another issue was that while Sam and Mary had cordial relations with the Mexican elite of San Antonio, they were not close friends. Mary noted that while they exchanged calls with leading families such as the Navarros, Seguins, Veramindis, and Yturris, she "never felt like being at all intimate." She did not want the children to spend much time with the children of the Mexican elites "because they let theirs go almost naked." Mary thus sketched out the gulf between the mores of Victorian-era Anglos and Mexicans. And given that these families all lived on or near the Main Plaza, the Mavericks were apparently not disturbed at the thought of moving farther away.

The family moved in July 1849 from the Main Plaza to the Alamo Plaza. Sam had acquired land near the old mission church and convento, at the northwestern edge of the plaza in 1841. Between 1844 and 1849 he bought four large parcels of land between the Alamo Plaza and the San Antonio River. At first the family occupied "an old Mexican house" on the west side of the plaza and on the south side of what would become Houston Street, across from the site where they would build their new house.

Indeed, this house probably incorporated a room (or rooms) from the west wall of the mission enclosure, which had served one hundred years before as apartments for Indian converts. It was bounded on the north and west by the Alamo acequia, which was by then abandoned. The Mavericks would spend nearly a year and a half in this house, as work did not begin on the new house until June 1850, and they did not move in until the first of December. Mary did not note any changes the family made to the house; perhaps all their energy went into planning the new structure. Indeed, her only comment about their latest temporary abode was made in connection with the new house, which they found "very nice, after the old Mexican quarters we had occupied for over a year."

The neighborhood into which they moved was not only predominantly Mexican but also predominantly poor. When Frederick Law Olmsted visited town in 1854, he found the Alamo "a mere wreck of its former grandeur," and in use as an arsenal by the U.S. Quartermaster. He described the Alamo Plaza as "all Mexican. Windowless cabins of stakes, plastered with mud and roofed with river-grass, or 'tula'; or low, windowless, but better thatched, houses of adobes (gray, unburnt bricks), with groups of brown idlers lounging at their doors." Interestingly, Olmsted chose not to mention the Maverick House, sitting prominently at the northwest corner of the plaza.

Sam and Mary Maverick moved with an awareness that things were changing on the Alamo Plaza, however. In 1849 the U.S. Department of War named San Antonio headquarters for all army operations in Texas, and on January 1, 1850, Jean Marie Odin, the Catholic Bishop of Texas, agreed to rent the entire Alamo compound to the army for $150 per month. Maj. Edwin Burr Babbitt, the chief quartermaster for San Antonio, recommended to Gen. Thomas S. Jessup that the Alamo buildings be demolished and new ones erected, but Jessup overruled this suggestion. In the spring of 1850 Babbitt reroofed the mission church, adding a second floor and a curvilinear parapet. Maverick also rented an adjacent lot to the army for $20 per month. The mission church was used for the rather mundane purpose of storing foodstuffs, but the army's occupancy meant that the building would not deteriorate any further. Others also saw the eastern side of town as ripe for redevelopment: in 1859 John Fries and J.H. Kampmann began to build a large new hotel, to be known as the Menger Hotel, just south of the Alamo. In that same year, Sam Maverick acquired another large parcel of land northwest of Alamo Plaza; from this land the Mavericks would eventually donate Travis Park to the city, and, on the north side of the park, the site for St. Mark's Episcopal Church.

Ultimately, though, the selection of Alamo Plaza as the site for the Maverick House was a very personal one for Sam Maverick. In an 1846 letter to Mary, Sam referred to the Alamo as "the old Golgotha." This Aramaic word for skull denotes the hill where Jesus Christ was crucified, known in its Latin form as Calvary. In more modern times Golgotha had taken on the connotations of a graveyard or charnel house. Maverick thus remained intensely aware of the human sacrifice that had taken place on that spot little more than a decade earlier and may have been using the term not only in its generic sense, but also to draw an analogy between the sacrifice of the Alamo defenders and Christ himself. The next year he wrote to S.M. Howe, a U.S. Army officer in San Antonio, "I have a desire to reside on this particular spot, a foolish prejudice no doubt as I was almost a solitary escape[e] from the Alamo massacre having been sent by those unfortunate men [to the independence convention]." If Sam and Mary had their bedchamber in the south room upstairs, they may well have had a remarkable view of the old mission that had played such a memorable role in their own lives and in the history of their state.

An 1877 photograph shows that the Maverick House was a two-story block with the gables at the north and south end and a two-story gallery on the west side. The south wall had one window on each floor, and the longer west side had three per floor. The roof began several feet above the lintels of the second floor window, suggesting that the attic contained usable space. No dormers were visible, but the gable end has what appears to be a ventilator. The narrowness of the chimney suggests that it served cast-iron stoves rather than traditional fireplaces. Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps of 1885 and 1888, when the property had become a boardinghouse, make sense of the outbuildings visible in the photograph and document features not visible in the photograph.

The two-story gallery was actually L-shaped, attaching the main block of the house to a two-story kitchen. Connecting the main house and kitchen with a gallery was fairly typical in larger houses in Texas and, indeed, elsewhere in the South, but less typical was the fact that the kitchen was not situated behind the main house, but to the north and west of the main block. The longer south façade of the kitchen looked toward Houston Street, so that the main block and kitchen formed a courtyard.

The second floor of the kitchen may have housed some of the Mavericks' enslaved servants, but it could also have been separate living quarters for the older Maverick boys. Samuel was thirteen in 1850 and Lewis was eleven, though at five and three George and William were rather young to be apart from their parents. Whatever the function of the upper room of the kitchen block, the Sanborn Maps also indicate the presence of a one-story building north of the main house, with a south-facing front porch and a connector to the main house. This northernmost building may have housed the male slaves, just as room north of the zaguan had housed them in the old house on Main Plaza. Even in the 1880s, when the property was a boardinghouse, this building was labeled as a "servant's room." The Sanborn Maps cannot tell us whether either the kitchen or the servant's room date to 1850, but both are visible in an 1873 bird's-eye view of the city.

By this time, Sam had passed away but Mary was living there; clearly these outbuildings had been there for some time.

A final outbuilding is known through both the photograph and the Sanborn Maps: the Maverick Land Office. This was a low-roofed one-story building with front and back rooms, both lit by eastern windows. The door opened directly onto Houston Street, meaning that visitors to the land office did not have to enter the yard of the house. At the old house on the Main Plaza, the office was in the main block of the house nearest the plaza, but here the commercial aspects of the complex were strictly separated from the residential.

The Sanborn Maps also reveal that most of the buildings in the Maverick compound were made of stone: the main house, kitchen, servant's room, and land office. The only frame structures were two small outbuildings, one west of the kitchen and another west of the servant's room. The use of stone was traditional in important San Antonio buildings, such as the eighteenth-century missions and the residence of the presidio commander, though poorer folk lived in one-room jacales, with walls of wooden posts driven into the ground.

The form of the Maverick House was highly unusual for an Anglo family in San Antonio. The house of John James, a business partner of Maverick's, was a far more typical Anglo Texan house. James's main house was a squarish block set back from the street, with galleries on both the front and rear elevations; the kitchen, a separate building behind the main house, had only a front gallery. Both the first floor of the main house and the kitchen were built of stone; later Sanborn Maps show a frame second floor to the main house, which may have been a later addition. Both the way in which the James House related to the street and the relation between house and kitchen marked it as being more conventionally Anglo Texan.

An even more imposing Anglo Texan house was that of James Vance, a New York-born merchant and banker. This house, built south of the Main Plaza, was two stories high and had a partially submerged basement. Both the principal front, facing in the direction of the plaza, and the rear elevation had colonnades with Greek Revival box columns. A central passage with a staircase ran through the house on the ground floor and the upper two floors. The entire house was built of stone, and family tradition claims that the architect builder was John Fries, a German stonemason. Olmsted observed that "the American dwellings stand back, with galleries and jalousies and a garden picket fence against the walk," which could describe the James, Vance, or Maverick houses.

The Maverick house in San Antonio was also different from that designed by relatives back in South Carolina. Montpelier, Sam's father's house in Pendleton, in the western part of the state, burned early in 1850. The senior Maverick had recently suffered a stroke, and so the task of rebuilding fell to his son-in-law William Van Wyck. The new house, built a short distance from the old one, featured a central passage and four rooms downstairs and up, a plan characteristic of many Greek Revival, Federal, and Georgian houses. Four square piers create a two-story central portico; more unusual was the cast-iron balcony to the right of the entrance portico, which opened into the drawing room. Although the Maverick-Van Wyck house was some 245 miles inland from Charleston, it featured a typical central passage plan and fashionable neoclassical ornament.

The Maverick house was unlike other Anglo Texan houses in San Antonio or the house of Sam's brother-in-law in South Carolina; however, the house possessed a number of characteristics associated with the house form known as the Charleston single house.